Interviewed by Daniella Romano • Brooklyn Navy Yard Archive • December 8, 2008

In memory of Howard Zinn and in appreciation of his life’s work, the Brooklyn Historical Society and the Brooklyn Navy Yard Development Corporation shared excerpts from an interview they conducted with Howard Zinn.

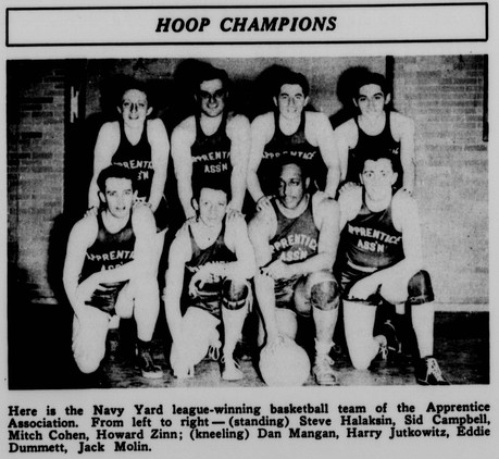

In this interview, Zinn shares detailed memories about growing up in Brooklyn, working as an apprentice shipfitter in the Brooklyn Navy Yard, helping to organize an apprentice shipfitter association, organizing a winning basketball team, and his first date with Roslyn Shechter , his future wife.

The interview was conducted by Daniella Romano, director of the Brooklyn Navy Yard Archive. Listen to the full audio interview at the Brooklyn Historical Society, complete with transcript.

TRANSCRIPT

ROMANO: Today is Monday, December 8, 2008, and we are conducting an oral history interview at the Brooklyn Navy Yard with Howard Zinn. Um, and I’ll just start with please tell me what —

[Interview interrupted.]

ROMANO: Okay, um. Tell me where and when you were born.

ZINN: I was born in Brooklyn, 1922.

ROMANO: Mm-hmm. What is your family background?

ZINN: My, my parents were immigrants from Europe. My mother came from — they’re both sort of Jewish working-class people, came here. My father came from the Austro-Hungarian Empire, probably the part that’s now Poland. My mother came from Siberia, from the city of Irkutsk. And they came here and worked as — they were factory workers in New York. They met as factory workers and got married 1:00and then they moved to Brooklyn. And that’s where I was born.

ROMANO: Where in Brooklyn?

ZINN: I was born in actually, it’s sort of — what was then called, I guess, part of Williamsburg, but I don’t know what they would call it now. De — sort of Floyd Street, which was near Stockton Street, not far from DeKalb Avenue. I’m just rattling off some of the streets that were nearby to get an idea.

ROMANO: Floyd and Stockton aren’t familiar to me, but of course DeKalb is just up the —

ZINN: Yeah.

ROMANO: When did you come to the Brooklyn Navy Yard?

ZINN: Yeah, well I — um — it was 1940. I was eighteen. Young people were 2:00desperate for jobs and my background, my neighborhood — my situation, kids didn’t go to college at the age of eighteen, they went to work. And so, I took a test. They announced there was a civil service test to become an apprentice in the Brooklyn Navy Yard and, like, I don’t know how many thousands of young people took that test. I think — I think 30,000 young people took the test for 400 jobs. And the 400 guys who got 100 on the test got the jobs. And so, I was one of those 400, so I was one of 400 young people who then went to work as apprentices in the Navy Yard in 1940.

ROMANO: Which area did you work in?

ZINN: I became an apprentice ship fitter. We all were assigned, rather arbitrarily. Some became ship fitters, some became joiners. A joiner, I learned — I had no idea what a joiner was — a joiner, I learned, you know, worked with wood. Shipwrights, machinists, and pattern makers who were more white-collared people, worked with blueprints. So, the apprentices were divided along these different specialties and so I soon found myself working as an apprentice ship fitter with a real ship fitter, a senior ship fitter. And we had a little team of the ship fitter, his apprentice — me — and then working with us and around 4:00us, a welder, a riveter, a burner, a chipper. I soon learned what all of these people did, you know. The ship fitter had the job of fitting the steel plates of the hull together in the right way. Like a kid working with a jigsaw puzzle. Working with blueprints and the rigger was the person who worked the huge cranes that lifted these metal plates into place and so the rigger would lift the metal plates into the right place and the ship fitter would decide where it belongs and move it this way or that way according to blue print and then call in the — well, first do some tack welds. That’s what some of the apprentices did, also. A tack weld was a sort of temporary little inch of a weld to keep the plate in 5:00place until the welder came along and did the real weld. Or if not the welder, the riveter came along. The riveter was working on things which made it actually more secure than a welder. A weld could be broken more easily than something that was riveted. So, the welder, the riveter. And we would have the burner, somebody with an acetylene torch, who would cut the steel plate down to size. And the chipper was another person, who using a compressed air hammer, would make a tremendous noise, an enormously powerful tool. Because it had to drive a chisel into the steel and cut off edges of the steel. And generally — generally the people who were the chippers and the riveters who did the heaviest, toughest work — because the riveting machine was a huge — not like these little riveting machines you see in, doing — not like the ones that worked on sheet 6:00metal. Riveting machines which had to put rivets into these thick, steel plates, required a very powerful person to hold onto this huge riveting machine and as he used it his body would vibrate with the riveting machine. And the guys who were the riveters and the chippers were usually blacks who were hired to do the toughest jobs in the Yard.

ROMANO: What would you wear? What was your uniform?

ZINN: [laughter] My, my uniform. I like that word, uniform. We wore very — well, in the winter we wore very warm clothes. Layers of clothing. I wore — we had steel-tipped shoes because of all these metal things falling on our toes. We had steel-tipped shoes and warm double layers of, you know, winter underwear, 7:00double layers of clothes and hats with earmuffs — hats that went over our ears — and heavy gloves. Because we were working out on the ways. It was working out on this long, inclined surface on which we built the hull of the ship so that when the ship was built — not totally built but built enough so that they then work on the, you know, on the decks of the ships. But after the hull was built and the ship was going to be launched, it would be launched, it would slide down in the ways into the water. So, the ways were out there on the river, really, and the cold wind blowing in from the river. So, it was very, very cold. And we 8:00would, in order to keep warm, we would huddle around the riveter’s fire. Because the riveter had a little fire on which he heated his rivets before — with his clamps. Where he put the heated rivet into the rivet hole, so then when the heated rivet cooled it of course then fastened the plates. But we went around the riveter’s fire in order to keep warm. Or we went into the head to keep warm. The head meaning — you know the head is the toilet. One of our favorite places. And, uh, and then in the summer it was very hot. Very, very hot. Because we were wearing protective clothing and I remember that they gave us salt pills in the summertime to, uh, because we were sweating, sweating. And we were sweating not 9:00only because of the heat but because a lot of our job required us to crawl into the hull into these little compartments which were four by four by four and which had a little hole through which you could go into this four by four by four apartment to work to do a tack weld, to check up on whether it was right, and so it was very, very hot. You sweated a lot and so you had these salt pills to apparently make up for the salt you were using in all the sweating. But, you know, we spent a lot of the time crawling into this — well, it was called the double bottom of the hull. Because we — when I went to work there, they were just starting to build the USS Iowa. Starting to build meant starting with the keel. And when I see–think of a keel today, I think of something in a sailboat 10:00that you know, which is a protrusion down into the water, but what they called a keel in the building of the Iowa, and the building of the battleships, was not that. They called the very bottom of the ship, the double bottom of the battleship, they called that the keel. And that’s what we started working on. And the keel consisted of all these compartments and the idea being that when — if one compartment got flooded it would be confined to that compartment and so you wouldn’t be flooding the entire double bottom of the ship.

ROMANO: Um, the keeling is a ceremony often, right?

ZINN: What’s that?

ROMANO: Were you at any ceremonies?

ZINN: No.

ROMANO: Did you go to any launchings.

ZINN: No, no. I did not attend any keel — no, I — for some — I don’t know why. [laughter] We weren’t invited to the ceremonies. No, but when we finished I 11:00knew that there was a ceremony for the launching of the Iowa but I wasn’t there, because then the next thing we did after the Iowa was launched, started building the Missouri. Which was the ship that, you know, became famous as the ship that the surrender was signed by the Japanese and the U.S. at the end of World War II. I worked on the Missouri just for a while and actually then, come to think of it, I also worked on — for a while — on building LSTs which were landing ship tanks. They were strange little ships that — they looked rather flimsy — well, they were made of steel, but they were just big enough to hold one tank, and they were going to be used in D-Day. To have, you know, thousands of LSTs 12:00bring tanks onto the beaches of Normandy. So, we built — we built a number of those and then at a certain point in early 1943, I stopped working in the Yard because I enlisted in the Air Force. I actually — I could have stayed because we were — you know, we were considered important war workers and we were exempt from the draft but I wanted to — I wanted to go. I wanted to fight in the Great War and all of against fascism and all of that, so I enlisted in the Air Force and that’s when I left the Yard.

ROMANO: I have a lot of questions. [laughter]

ZINN: Okay.

ROMANO: Did you work with any women if you left in early ’43?

ZINN: No. There were no women working out on the ways. There were women who 13:00worked in sort of office capacities, administrative jobs, but I didn’t — I never saw any woman working — and course there were thousands of people working. I mean, working on the Battleship Iowa was an enormous operation. The Battleship Iowa, when you — if you stood it on end, which was almost as tall as the Empire State Building. This was sort of — this always astounded me when I thought of it — that it was as long as the Empire State Building was tall. So, it was a huge, huge place. Thousands of people worked on it. But I never saw a woman working on it. And maybe there were women later who worked — maybe not out on the ways or maybe not as ship fitters, but maybe there were women who worked as machinists. I heard that in 1944, which was after I was gone, there were women machinists. But I didn’t know any women. In fact, we had an appre — 14:00there were no women apprentices, because we had an apprentice association, which was another aspect of my life in the Navy Yard, which actually to me was the most interesting aspect of my life in the Navy Yard. The most uninteresting was work.

[laughter]

ZINN: The most uninteresting and the hardest and the toughest. I must say this, that when I first — the first day I walked into the Navy Yard, it was an amazing experience because I had never walked into a situation — the first time I walked out on the ways, I was walking into a kind of nightmare of sounds, noise, and smells. The smells of working on a ship are amazing smells. The 15:00smells of the welding, especially — when they were welding galvanized steel. I don’t know if you’ve ever smelled galvanized steel burning because galvanized steel is covered with zinc and you — when zinc burns it gives off the worst smell in the world. [laughter] So that and other smells. And the noise of the riveting and the chipping. It was just — it was nightmarish. It was something I had to get used to. And so, work was not — very often we wore earplugs because of the sound was so horrendous. And so yes, work — work was not a satisfying 16:00experience. It was not — not like — you know, here I was building a beautiful little ship. You know, you have these people who have hobbies of building boats and, “Whoa, what a nice experience it is putting little things together.” No, this was not a pleasant experience. I didn’t even know what the whole thing would look like when it was over. I was just working on a little part of this big, steel ship and it — no, it wasn’t terribly satisfying. And — but what was satisfying was finding the other apprentices, the other ship fitter apprentices, the other apprentices in the other areas — the machinists and the shipwrights and the joiners — and joining together with them and forming an association 17:00because the apprentices were not permitted to join the unions. At that time, the unions in the Navy Yard were part of the AF of L, the American Federation of Labor. The American Federation of Labor was a federation of craft unions and craft unions meant that the unions were divided by skills. And so, the unions in the Navy Yard were all separate. The machinist union and the shipwrights union and the joiners union and the boilermakers union, ship fitters union. These were all separate unions. The craft unions. And you had to be a sort of accepted and experienced ship fitter or shipwright in order to join the union, which meant that there was no room in the union for apprentices, for helpers — and there 18:00were helpers by the way, blacks were helpers. There were no blacks in the actual unions. Blacks were helpers, which meant they were chippers or riveters. And the apprentices, um, were not in the union. Now the reason that in the 1930s the CIO came into being is they came into being because there were so many workers in the country who were not organized because they were not admitted into the AF of L craft unions. There was a huge number of unskilled workers, which included women and black people in the auto industry and so on, who were not in the union, so the CIO had this enormous reservoir of unskilled workers that they organized into unions. And of course, the CIO became the militant labor union in 19:00the 1930s that was really the heart of the new angry, striking labor movement at that time. Well, we — well, there was actually a CIO union that tried to move in and organize in the Navy Yard, but they didn’t get very far. They were called — in fact, I was a member, which means I was a member of a very tiny and weak organization. I was a member of something with a very poetic name of IUMSWA, the Industrial Union of Marine and Shipbuilding Workers of America. And I think part of the reason they didn’t have any members is that nobody could pronounce that, you see. So — but we, the apprentices, decided we had to organize. I was getting fourteen dollars a week, which after deductions, it was something like 20:00twelve dollars and something. And I would give ten dollars to my mother and father and keep two dollars of spending money for myself. So, we were getting fourteen dollars a week and we decided we needed to get more money and, you know, be organized and be able to bargain with the Navy Yard for, you know, certain conditions. And so, uh, we organized this apprentice association. And I was one of the initial organizers. The initial organizers were a little group of young radicals, I must say. I must confess. A little group of young radicals who decided we would organize the apprentices, and we did. So we formed this 21:00apprentice association of you know, 300 or 400 apprentices and those — that little organizing group that initiated it, you know, and — there was me and there was a guy who was a machinist and there was another guy who was a shipwright and there was another guy who was sheet metal worker. And the four of us would meet once a week, outside of work, and talk about organizing, and also, we would read books and discuss these books. Radical books. [laughter]

ROMANO: Like what?

ZINN: Political books. Who? Well, we would read Upton Sinclair, Jack London, and Karl Marx. [laughter] So um, yeah, we would read and discuss and yes, we were 22:00the organizers. My job was activities director, of which I had a huge amount of experience. That is — zero. Activities director. My job was to plan activities that would raise funds for the association. So, actually, I was part of two activities that we engaged in because I also organized a basketball team, and I was one of the members of the basketball team, not because I organized it but because I was a fairly good basketball player. At that time, I was six-foot-two. I think now I’m five-foot-two. No, I’m not — I’m just a little less. But at that time, I was six-foot-two. At that time, you didn’t have to be seven feet 23:00tall to be a basketball player. Six-foot-two was okay. So I organized a basketball team and we formed an apprentice basketball team and we played basketball teams that were formed by the other — the unions, the older people who were — older meant they were in their thirties or forties, and they were the carpenters and — we won, hands down. We were the youngest, we were the fastest. We won the championship — we were the Brooklyn Navy Yard champion basketball team. And the other thing that I organized was a moonlight sail and — to raise money. A moonlight sail on the Hudson River. The Hudson River was as close as we could get to the Rivera. And the, uh, so — and it was on that moonlight sail that I had my first date with my future wife. So —

ROMANO: How did you organize the sail?

ZINN: Well, organizing the sail meant just writing to all the relatives of the — you know, notifying — the apprentices notifying the other people in the Yard, you know, writing, getting names and addresses and sending out letters. We didn’t have e-mail or fax machines or anything like that. So, we used old-fashioned ways and rented this boat and it was a beautiful moonlight sail. Yeah.

ROMANO: Organizing the apprentices, did you have any mentors in the union? Did you have any older —

ZINN: No. No.

ROMANO: — figures who were helping you and guiding you?

ZINN: No, we didn’t. We were on our own. But a couple of us — as I said, we were four young radicals and a couple of us had actually been sort of active in our neighborhoods before that. Politically active and you know — uh —

ROMANO: HQ your parents — were your parents part of any unions?

ZINN: My parents?

ROMANO: Yes. Was there a family tradition of organizing, or — ?

ZINN: No. No. Well — my parents were not political people. They were not radicals, they were just very ordinary, you might say. Working-class people and — but my father was — my father was a waiter. That is, he moved up in rank 26:00from being a factory worker to being a waiter. And as a waiter he was a member of the Waiters Union. Local 2 of the Waiters Union, which was a Brooklyn local that specialized in Jewish weddings and bar mitzvahs. And, uh, so that was — yes. So, he was a union member. And there was some vague connection between his union and some bunch of gangsters who extorted money from people in the union in order to get them jobs. Just, you know, part of the history of unionism.

ROMANO: You are just going through my list very naturally without my having to ask questions, but I do want to know, if you were living in Williamsburg how did 27:00you come into work every day? Were you walking, did you ride a bicycle, did you take the trolley?

ZINN: My, my family got a place in the Fort Greene housing project, which gave preference to people who worked in the Navy Yard. My family had lived in miserable places in Brooklyn and going, moving into a housing project was a real step upward. These were clean places that didn’t have vermin and rats and so they were very desirable. Well, these low-income housing projects, which today very often have a sort of bad reputation; they’re run down and dirty — and this is what I hear, I haven’t been in them lately. But when those housing — 28:00low-income housing projects were built they were so desirable that all these people living in terrible tenements in Brooklyn were vying for these places in these housing projects. And so, my family — my mother and father — were very happy to be able to move into the Fort Greene housing project, and when they did that, I could walk from the project to the Navy Yard. Every morning my mother would prepare my lunch. I carried one of these little metal lunch containers and it had room in it for a thermos of hot coffee, which my mother put milk and sugar, and it was sort of all morning I was only thinking of lunch time, while working. All morning — you know, this happens a lot I think with people who work, and they are looking forward to lunchtime, they’re looking forward to 29:00leaving work. There’s something they look forward to because they’re not looking forward to the next hour of work. And so, my mother always prepared a very nice sandwich for me. Usually it was a fried-egg sandwich, my favorite sandwich. And a banana, and this thermos of real hot, delicious coffee. So, I carried my little lunch pail with me, and, uh, we began to work long hours. Because when I first got into the Navy Yard, we were working an eight-hour day. But soon we were asked to work ten hours, and soon twelve hours. And first it was a five-day week, then it was a six-day week. And then we were asked to work seven days. And actually, we were glad to work long hours — I mean, we were asked to do it as a 30:00patriotic duty, which in a — I guess partly was helpful in getting us to agree to work those long hours. Yeah. They need these ships. The boys are over there fighting, and etc., etc. So, part of it was this, this feeling, yes, we’re doing something patriotic for — the other and maybe the more important part for us was that by working overtime we were getting time and a half and that fourteen dollars expanded into twenty-five and thirty dollars by working those extra hours. So, we were making good money by working those extra hours. But it also meant there was nothing else in our lives but work. Um —

ROMANO: Was your pay going up, too? Was your pay rate going up, too?

ZINN: The pay rate went up. Yes, the pay rate went up gradually over those 31:00several years that I worked there, but you know, I don’t remember ever bringing home a paycheck more than thirty-five dollars. But that was really good, and the family really needed it. Because in the Depression — and the Depression was still going on, you know, really. Although it began to ease as the War went on but during the Depression the waiters did not have as much work. People made less weddings, or less expensive weddings. People still got married but they didn’t have weddings with a lot of waiters and so on. So, the family needed the money. So, I became, you might say, you know, the chief wage earner in the family. And so, in a certain sense, by joining the Air Force, I was depriving my 32:00family of that. Except that I — even though I wasn’t making much money in the Air Force, I would send a good part — since the Air Force was feeding me, clothing me, giving me a place to sleep, so I was able to give a good part of my Air Force money, send it home every month to, uh, my parents.

ROMANO: Your parents got to stay in the Fort Greene housing?

ZINN: They did. Yeah.

ROMANO: You had been their connection to live there. If there was preference to the Navy —

ZINN: That’s right. But they still were able to stay. They weren’t evicted from there because I left the Yard.

ROMANO: Okay. Did any of your co-workers, did any of your fellow apprentices also leave, to go serve? Or did they just stay on?

ZINN: Some of them stayed, some of them left. The more politically aware, the 33:00little group that I was in — as I said, they were the political radicals. And because they were more politically aware, they were more attuned to this is a war against fascism, you know, and so the other three guys who were a part of our little four-person collective, you might say, the other three guys also went into the service. They all went in after I did, but they — all three of them went into the Navy. Maybe it’s because the Navy was able to use their Navy Yard skills, whereas — well, I volunteered for the Air Force. And so, yes, the three of them went into the Navy and I was in the Air Force. And we communicated with one another for a while and after the War I would see them occasionally.

ROMANO: That’s what I was going to ask next, do you stay in touch with any of them today? Would there be [inaudible]?

ZINN: I lost touch with them. There was one of them that I made contact with, uh, maybe, uh, ten years ago and yes, they might all be dead. I say that because most of the people who are my contemporaries are dead, you know. I am a rare survivor. So, I don’t know what’s happened — yeah.

ROMANO: Well, maybe I could take some names, too, later. I’m trying to find people. Because we are still looking to conduct interviews.

ZINN: I could give you some names.

ROMANO: Okay. That would be great. Let’s see, so we talked about what you had 35:00for lunch. Is that all you ate? Was a fried-egg sandwich and a banana? That whole long day? For a six-foot-two guy. Did you snack, too? You must have.

ZINN: There was a little PX where we could get sort of candy and things like that, you know. And that was about it. Yes, but that was the only meal I had while working.

ROMANO: Um, who was your supervisor?

ZINN: I have no idea. [laughter] I stayed away from the supervisor as much as possible. The supervisor would occasionally — occasionally come around. We didn’t have a lot of supervision. The supervisor would occasionally come around and, you know, and sometimes he would go to the head — I think he spent a lot of time inspecting the head — and see who was there. He was spending too time in the head. But, you know, my immediate contact was with my — the ship fitter. 36:00The ship fitter was usually somebody who was from Scotland or Germany, from some country where there was a tradition of shipbuilding and where, you know, people learned these skills. And so, there were these immigrants from Scotland and Germany, Holland — places that were — you know, that had ports and had long historic traditions of shipbuilding. Uh —

ROMANO: That was going to be my next question was how would you describe the racial or cultural mix?

ZINN: Yeah, well, as I said, you know, all, all white people had the major jobs and they were the regular ship fitters and shipwrights and so on, and the blacks 37:00were the riveters and chipper, really. No women — there were no women workers and um —

ROMANO: And then the German, or the Scotch, your ship fitter, what was it like working with — did he have a heavy accent usually — or how did you communicate with him?

ZINN: Yes, my ship fitter, yeah, my guy had a heavy German accent. I suspected him of being a Nazi. [laughter] At least he behaved like a, he behaved like a Nazi.

ROMANO: How?

ZINN: Well, very arrogant. In fact, in general the apprentices were treated with a certain amount of humiliation. In fact, we were called “apprentice boys.” Yes, 38:00we were treated like — yeah, very arrogant. You know, they were the one who knew their trade, knew the craft and they were teaching us, and we were the stupid ones. And so yes, there was a lot of that. Yeah, there may have been some kindly, gentle workers but I never ran into them. And none of the guys I knew ran into them. Everybody complained about the way they were treated. There was this hierarchy. I think the AF of L union sort of encouraged that hierarchy. “We’re the skilled workers who belong to the union. These are the unwashed, unskilled, interlopers.” You know.

ROMANO: Were you fellow apprentices all mostly from the neighborhood, too?

ZINN: No, they came from all over the city. Because the civil service test was, 39:00you know, a city-wide test so they came from all — from the Bronx, and from Manhattan, Queens.

ROMANO: So, then you would socialize with your fellow apprentices. Ever with the ship fitter or — or any of the skilled — ?

ZINN: Well, we socialized after work in these, you know, events that we would create, you know, that we would organize, whether it was a dance or a moonlight sail or the basketball games. You know. Those were the times when we would get together outside of work.

ROMANO: Did you get together to go to dinner or would you go to any bars or would you go — ?

ZINN: No. I would like to imagine us as tough guys leaving the Yard, going to bars and drinking, but no. No. I think most of these guys were in the same position that I was. They had mothers and fathers waiting for them at home. And 40:00going to a restaurant for dinner was something we didn’t even think about.

ROMANO: There is Sands Street outside of the Yard; the infamous Sands Street. It’s got quite a reputation for, during World War II, being a popular spot for gambling, bars, bar brawling, prostitution. Kind of like a blue light district.

ZINN: Yes, we heard of Sands Street. We knew about it, but we actually didn’t have time to go there. Maybe if we had time, we would have had that experience. But no, it was — and maybe some of the older people in the shipyard went there. Had the money to go there. But, no, we knew about it but that’s all.

ROMANO: Um, do you have any particularly vivid memories or colorful memories or 41:00are there any people who really stand out? Like what would you say, I mean, your experiences with the apprentice association, was your most powerful experience?

ZINN: Yes, you know, the experience with the apprentice association was the most rewarding, getting together with other young people and organizing and planning our strategies and our — putting together our grievances. Putting out a little, you know, newsletter of some sort. I mean, the other experiences were on the job, not good ones. Like seeing people injured, seeing people fall into, you know, off a — very often after you walked along steel girders and below you 42:00was, you know, a big gap and there were people who fell and were badly injured. And there was the one time I remember, the worst thing I saw was somebody directing the crane operator and the crane operator’s also operating this huge steel doors and, uh, this was not on the ship, this was in a building outside where they were keeping a lot of the steel plates. And there was a guy who was directing the crane operator and as he was directing the crane operator he was walking backward and didn’t see where he was — and he was walking right in 43:00between the doors as the doors were closing and they closed on him. These huge, huge doors closed on him. And the guy who was up there operating the crane didn’t see him. And the guy was crushed to death. So that was the worst thing I saw.

ROMANO: You saw that?

ZINN: There were other little injuries of guys who looked wrong — at the wrong time looked at a welder’s flash and got, you know, actually I still have in one of my eyes a little — one of my eyes is a little blood shot which goes back to looking too long at a welder’s flash. And I mean, who knows what other physical effects there were from working in the shipyard. Because, um, the zinc actually 44:00was deadly, which we didn’t know at the time. But years, years later they found that there were people who worked with that zinc — and I wasn’t working with it all the time, just occasionally smelled it and got away from it as fast as I could — but people who worked a lot with that zinc, years later they discovered they developed cancers and died as a result. But I mean, industrial work is dangerous, unpleasant, and people die earlier. Um, and I was glad to get out of that. The Air Force was respite. [laughter]

ROMANO: Why did you choose the Air Force?

ZINN: I don’t even know. I had never built a model airplane in my life. I wasn’t 45:00particularly — I think maybe because a friend of mine who had gone into the military earlier — a friend of mine was in the Air Force and he was writing letters back. And I guess it seemed a little more glamorous to be in the Air Force than to be on the ground. But that was, I didn’t have any strong reason. People didn’t generally volunteer for the infantry. They, you know, when people volunteered, it was for the Navy or the Coast Guard or the Marines or the Air Force. So somehow, I chose the Air Force.

ROMANO: Um, to get back to the cultural mix and the ethnic mix of people who you were working with, blacks were obviously aware that they weren’t allowed into the union. Was there — did you talk to many of your co-workers who were African 46:00American and find out that they — what was the sense of that sort of separation, the segregation, really?

ZINN: Well, now we talked — we talked to the black guys who were riveters and chippers and, you know, they just shrugged their shoulders. You know, that’s the way it is. That’s the — nothing strange to them. A number of them came from the South. They were accustomed to segregation. Well, and of course, even black people in the North were accustomed to segregation. You know, the neighborhoods we lived in, in Brooklyn, were segregated. Black people lived under the El, lived under the Myrtle Avenue El. I don’t know if there’s a Myrtle Avenue El anymore. I don’t know if there’s any els anymore in Brooklyn. But the els, it 47:00was the elevated line and under the elevated line the people lived in the tenements that were right under the El, they lived in darkness all the time. There was no sun that came into the El, and that’s where black people lived. And they moved out of there — that is they didn’t move out of their places — they left their living place during the day to go to work, in the white neighborhoods. So, they worked as janitors or whatever menial jobs in the white neighborhoods. It was very much like Johannesburg, South Africa. Which many, many years later I visited, and you could see the blacks lived in their little black shanty towns and come into Johannesburg to work during the day and then go back to their little black townships at night. And that’s the way it was in Brooklyn.

ROMANO: And so, on the Yard, were any of these guys talking about organizing or was it just such an accepted fact of life that they wouldn’t be able to get into the union?

ZINN: You mean the black guys talking about organizing? I never heard, no. Of course, it was very hard for them. They were separated by — I mean, of course, we were separated, too, the apprentices, but no, they didn’t talk about it. I didn’t see any moves that they made toward organizing.

ROMANO: Um, yeah, I told you we had interviewed another gentleman, African American, who was here as a machinist from ’44 to ’46 and he talked — he worked at the Yard twice: in the ’40s and then later on in the ’50s during the Korean War. And he said that in the ’40s he remembers having “C” and “W” badges. Do you 49:00remember anything like that? Like “C” as in colored and “W” as in white. That he remembered that there were badges that said “C” and “W.”

ZINN: No, no, no. No, I don’t remember badges. No. He recalls badges that they wore? “C” and “W,” really?

ROMANO: Yes.

ZINN: Um. No, I don’t remember that.

ROMANO: But you don’t recall anything like that?

ZINN: No.

ROMANO: So, it was an integrated, somewhat, environment but not in terms of the union?

ZINN: That’s right.

ROMANO: Okay. And then we talked a little bit about the climate in terms of people — the skilled laborers, or the skilled workers, and having a greater sense of arrogance —

ZINN: Yes.

ROMANO: — and, and ownership of the place. Anything else along those lines? Any sort of personalities that represent the Yard at that time to you? In your, like, I guess was there a greater sense of comaraderie, too, because of what you 50:00were working on and like patriotic — ?

ZINN: The camaraderie was not so much at the work site, but afterwards in the apprentice association. There was a camaraderie outside of work. Uh —

ROMANO: Okay, and a sense of, like, the ships that you were working. So, you knew what you were contributing to, of course, and we’ve talked about that too.

ZINN: Yes.

ROMANO: Um, I feel like, unless there’s anything else that you think we might have missed or that you want to volunteer or — I don’t know if you have any final thoughts. I’m really done with my questions.

ZINN: No, those were all good questions and I think I’ve covered the experience.

ROMANO: That’s great. Well, thank you very much. I really appreciate your time. Your clear memories.

ZINN: Sure. Well, I’m glad you’re doing this documentary.

ROMANO: It’s a wonderful experience. The people who we’re getting to meet and the experiences that we are collecting.

ZINN: Yes, you’re doing just what we were talking about last night at the Studs Terkel Memorial. Oral history. Yeah, it’s great. And I hope you will send me the finished movie.

ROMANO: Well, we’re not sure if it’s going to work into a movie right now.

ZINN: Oh, okay.

ROMANO: We want to produce an orientation film for the center, but it might also be, we might incorporate the interviews into the actual exhibit itself. Have a small screen where people can just get a snapshot. So, we’ll see. Right now the most important thing is just getting everything, and collecting, and then we will figure out how to tell the story once we have everything collected. So that’s it.

ZINN: Sounds good.

ROMANO: Thank you so much.

ZINN: Sure.

Brooklyn Navy Yard Archive • December 8, 2008