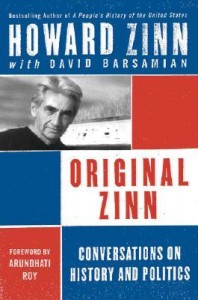

This interview was published in July 2004 issue of the The Sun magazine and is included in the book, Original Zinn: Conversations on History and Politics.

This interview was published in July 2004 issue of the The Sun magazine and is included in the book, Original Zinn: Conversations on History and Politics.

_________________________________________________________

Interview by David Barsamian

In an era when many academics seek safety and comfort by avoiding politics, Howard Zinn stands out as a model of the engaged activist-scholar. His unconventional perspective on U.S. history has made him one of the most beloved figures of the progressive movement.

Zinn grew up in a poor Jewish immigrant family in Brooklyn, New York. He remembers moving a lot when he was a child. “We were always one step ahead of the landlord,” he says. There were no books or magazines in Zinn’s childhood home; the first book he read outside of school was a damaged copy of Tarzan and the Jewels of Opar, which he found in the street. Despite this inauspicious beginning, he was soon a voracious reader. His parents, seeing his interest, clipped coupons from a newspaper offer and ordered him the complete works of Charles Dickens, one book at a time. When he was thirteen, they got him a used Underwood typewriter.

After graduating from high school, Zinn worked at the Brooklyn Navy Yard for several years. When the U.S. entered World War II, he joined the U.S. Air Force. His experience as a bombardier, destroying entire towns to get at small pockets of enemy troops, later provided material for his essays about the “stupidity of modern warfare.”

After the war ended, Zinn went to Columbia University on the GI Bill and earned his PhD in history. Then one day he heard a Woody Guthrie song about the Ludlow Massacre of 1914, one of the bloodiest labor battles in U.S. history. Twenty men, women, and children were killed when the Colorado Fuel and Iron Company used hired guns and militiamen to bring a violent end to a coal miners’ strike. Zinn had learned nothing about this important event from his professors or history books. Hearing that song was a defining moment for him. It inspired him to go beyond conventional academic sources in his history research.

Zinn taught at Spelman College, a historically black women’s college in Atlanta, Georgia, where he became involved in the civil-rights movement and was an advisor to members of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee; he was fired in 1963 for “insubordination” when he supported students in their protests. He went on to teach at Boston University, where he was a vocal opponent of the Vietnam War. He still teaches at BU and has been a fellow at Harvard University and a visiting professor at both the University of Paris and the University of Bologna.

Zinn is a history excavator. He digs for and recovers valuable and neglected aspects of the past, then uses them to help us understand the present. Zinn takes a bottom-up approach to history, giving voice to the stories of ordinary people, especially Native Americans, slaves, women, and blacks. He counters the academy’s top-down perspective with wry humor and devastating fact.

Today Zinn writes articles for Z magazine and a column for the Progressive titled “It Seems to Me.” His book A People’s History of the United States (HarperCollins) has sold more than a million copies, and each year sales exceed the previous year’s. He is the author of numerous other titles, including Failure to Quit (South End Press) and the autobiography You Can’t Be Neutral on a Moving Train (Beacon Press). His most recent book, Artists in Times of War (Seven Stories Press), reflects his keen interest in the arts. Zinn himself is a playwright who has written two plays: Marx in Soho and Emma, on the life of anarchist activist Emma Goldman.

Zinn lives with his wife, Roslyn, in Auburndale, Massachusetts. I talked with him in February 2004, after he had addressed an audience of trade-union leaders at Harvard.

Barsamian: You have called attention to the role of artists in a time of war. What attracts you to artists?

Zinn: Artists play a special role in social change. I first noticed this when I was a teenager and becoming politically aware for the first time. It was people in the arts who had the greatest emotional effect on me. I’m thinking primarily of singers: Pete Seeger, Woody Guthrie, Paul Robeson. I was reading Karl Marx and all sorts of subversive matter, but there was something special about the effect artists had on me—not only singers and musicians but poets, novelists, and people in the theater. It seemed to me that artists had a special power when they commented, either in their own work or outside their work, on what was happening in the world. There was a kind of force they brought into the discussion that mere prose could not match. The passion and emotion of poetry, music, and drama are rarely equaled in prose, even beautiful prose. I was struck by that at an early age.

Later, I came to think about the power of those in charge of society and the relative powerlessness of most other people, who become the victims of the decision makers. I thought about what tools people might have to resist those who have a monopoly on political and military power. Art, I saw, gave them a special motivation that couldn’t be calculated. Social movements all through history have used art to enhance what they do, to inspire people, to give them a vision, to bring them together and make them feel that they are part of a vibrant movement.

Very often, people who are not acquainted with the industrial workplace, people who have not worked in factories or mills, think that working people are not interested in literature. But working people have always had a life outside the workplace, and in that life many of them do read and become self-educated. Sometimes, at work, early-twentieth-century laborers would take whatever opportunity they had to talk to one another, to read to one another, to draw upon the great voices of literature for inspiration. In A People’s History of the United States, I quote from the memoir of a garment worker, who tells how she and her co-workers would read Percy Bysshe Shelley and quote these remarkable lines from his poem “The Mask of Anarchy”:

“Rise like Lions after slumber

In unvanquishable number—

Shake your chains to earth like dew

Which in sleep had fallen on you—

Ye are many—they are few.”

What a remarkable affirmation of the power of the seemingly powerless: “Ye are many—they are few.”

Barsamian: Shelley wrote that poem on the occasion of a massacre in Manchester, England, in 1819, when eleven peaceful demonstrators were shot and killed and hundreds more wounded while protesting against deplorable economic conditions. Shelley also wrote a famous poem about the arrogance and hubris of great emperors and titled it “Ozymandias,” which is Greek for “Ramses,” the ancient Pharaoh of Egypt:

“My name is Ozymandias, King of Kings,

Look on my Works, ye Mighty, and despair!”

Nothing beside remains. Round the decay

Of that colossal Wreck, boundless and bare

The lone and level sands stretch far away.

Zinn: I remember reading that poem in school, but much of its significance was lost on me. I don’t think the teacher drew out the full meaning of that poem, the trenchant critique of power. Power is temporary; it comes into being, and it goes out. Great monuments that look as if they will stand forever decay and fall. Shelley was certainly a politically aware poet, with connections to the anarchists of the time. He had some sympathy for the anarchist idea, which is based on, for one thing, the ephemeral nature of power and the fact that if enough people pool their meager resources, then they can overcome the most powerful force.

Barsamian: You also like to cite the poet Langston Hughes, who addresses the United States in a poem titled “Columbia.” What do you see in this particular poem?

Zinn: Langston Hughes is one of my favorite poets; he wrote poetry that got him in trouble with the Establishment. I see his poem “Columbia” as a forerunner, decades earlier, of Martin Luther King Jr.’s opposition to the Vietnam War.

Here, Hughes speaks out against the hubris of the United States as a new imperial power. He’s very skeptical of this country’s claims to innocence in its forays in the world. Addressing the U.S., he writes:

Columbia,

My dear girl,

You really haven’t been a virgin for so long.

It’s ludicrous to keep up the pretext.

You’re terribly involved in world assignations

And everybody knows it.

You’ve slept with all the big powers

In military uniforms,

And you’ve taken the sweet life

Of all the little brown fellows

In loincloths and cotton trousers.

When they’ve resisted,

You’ve yelled, “Rape.”

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

Being one of the world’s big vampires,

Why don’t you come on out and say so

Like Japan, and England, and France,

And all the other nymphomaniacs of power

Who’ve long since dropped their

Smoke screens of innocence

To sit frankly on a bed of bombs?

It has always been a special fascination to me that black people, who you might assume would be most concerned, and maybe solely concerned, with the very serious issues of slavery and racism, should also be conscious of what the United States is doing to people—often people of color—in other parts of the world. I think, for instance, of Zora Neale Hurston, a magnificent African American writer whom nobody could put in any kind of category. Very often she offended other black people by the things she would say. She was a totally honest person who spoke her mind and wasn’t afraid of going against the so-called wisdom of the day.

When World War II broke out, and everyone else jumped on the bandwagon to support the war, Hurston would not go along with it. She saw the war not as a conflict that pitted democratic, liberty-loving nations against fascist nations, but as a battle of one set of empires versus another set. In her autobiography, Dust Tracks on the Road, written shortly after the bombing of Pearl Harbor, she wrote that she could not get teary-eyed, as everyone else did, over what the Japanese and the Germans were doing to their subject peoples. It wasn’t that she approved of their actions, but she felt they were only doing what the Western powers—supposedly the “good guys” in the war—had done to their subject peoples: what the Dutch did in Indonesia, what the English did in India, what the Americans did in the Philippines. In Hurston’s eyes, they were all doing the same thing. Her publishers cut that section of her autobiography, and it wasn’t restored until many years after World War II. When the United States bombed Hiroshima and destroyed several hundred thousand human beings, Hurston called President Truman the “butcher of Asia.” Nobody else at the time was speaking that way about Harry Truman.

Barsamian: Let’s move on to more-contemporary artists. You like Bob Dylan and his “Masters of War.”

Zinn: Dylan is the great folk singer of the sixties, the civil-rights movement, and the Vietnam-era antiwar movement. There is probably no musical voice more powerful than his when it comes to expressing the indignation that generation felt toward racism and war. His songs continue to be played today, not only because of what they meant then, but because they are relevant to current crises. In “Masters of War,” which of course addresses the Vietnam War, Dylan could just as well be talking about the wars we have fought since Vietnam, and particularly the current war against Iraq. This song is still being sung, not just by Dylan but by many other singers, including Eddie Vedder of Pearl Jam, who is bringing Dylan’s message to a whole new generation:

Come, you Masters of War,

You that build all the guns,

You that build the death planes,

You that build the big bombs.

You that hide behind walls,

You that hide behind desks,

I just want you to know

I can see through your masks.

You that never done nothing

But build to destroy,

You play with my world

Like it’s your little toy.

You put a gun in my hand

And you hide from my eyes,

And you turn and run farther

When the fast bullets fly.

Barsamian: Another contemporary artist who has achieved enormous popularity is the filmmaker and writer Michael Moore, who’s had two bestselling books and received an Oscar for his documentary Bowling for Columbine. At the Academy Awards ceremony in March 2003, with a global audience of perhaps one billion people watching, he said, “Shame on you, Mr. Bush,” and denounced the U.S. attack on Iraq. Later, the Spanish filmmaker Pedro Almodóvar also made a strong antiwar statement. What do you think of these artists’ coming out and expressing themselves so forcefully?

Zinn: I think it’s admirable when artists make use of an occasion like the Oscars to speak out about what’s going on in the world. At the awards ceremony, the audience and recipients are supposed to immerse themselves in the spectacle of this Hollywood extravaganza, to shut out the world and feast on the glitter of what people are wearing and what awards they take away. In this context, it is “impolite” and “unprofessional” to mention that people are dying in other parts of the world. I admire those who refuse to abide by the rule that you must remain silent and be “professional.”

This rule about not going outside the boundaries of one’s profession is of great use to those in power. I have come up against it myself as a historian. I am supposed to talk just about history. When I showed up at the meeting of the American Historical Association in 1970 and proposed that we historians should speak out against the war in Vietnam, there was shock. “We’re historians,” people said. “We’re supposed to talk about history and present our papers and leave politics to the politicians.”

In the late eighteenth century, the French philosopher Jean Jacques Rousseau had something to say about this sort of abdication of social responsibility. He said, “We have all sorts of specialties; we have engineers, we have scientists, we have ministers, but we no longer have a citizen among us”—that is to say, somebody who will go beyond his or her professional prison and take part in the battle for social justice.

The people who do break out of that prison, like Michael Moore, deserve an enormous amount of credit. Entertainers have the ability to reach far greater numbers of people than the rest of us do, and if they don’t take advantage of it, they deprive us all of an opportunity for greater communication.

The musical group the Dixie Chicks were criticized for speaking out. One of them said she was ashamed to come from Texas, because it is George Bush’s home state. And the Academy Award–winning actress Jessica Lange spoke out at the Spanish equivalent of the Oscars, shortly after President Bush declared war on terrorism. In response to an audience member’s question, she said, “I despise George Bush and all that he stands for.” In Europe that kind of outspokenness is accepted—nearly every award recipient that year wore an antiwar button or banner—but according to American rules, she wasn’t supposed to do that. Like the Dixie Chicks and Michael Moore, she received a certain amount of criticism at home in the States.

I think celebrities should seize these opportunities more often. Although big stars may be condemned for speaking out on social issues, their talents are powerful enough to overcome that reaction: People still go to hear the Dixie Chicks. And people still buy Michael Moore’s books—in fact, they sold even better after the event. And people aren’t going to stop seeing Jessica Lange’s movies.

Barsamian: Molly Ivins, the syndicated columnist and coauthor of the bestseller Bushwhacked, reports meeting ordinary citizens who say, “I’m not interested in politics,” or, “There’s nothing I can do about it.” What do you say to people who feel there is no use in getting involved?

Zinn: I hear those cynical comments a lot, too. I might be speaking to an audience of fifteen hundred people, and someone will get up and say, “What can we do? We’re really helpless.” And I’ll say, “Look around: There are fifteen hundred people here who have just applauded me enthusiastically for speaking out against the war. And that’s just in this small community. Everywhere you go in the United States, there are fifteen hundred or two thousand people who feel the way you and I do. In fact, not only do they feel that way, but more and more of them are acting on their feelings. You might not know what they are doing, because the United States is a very big country, and the media do not report on the activities of ordinary people. They will report what the president ate yesterday, but they will not report the gathering of a thousand or two thousand people on behalf of some important issue.”

Now, whether these numbers can have an effect is something we can’t judge immediately. Here is where history comes in handy. If you look back at the development of social movements in history, you’ll find that they start with small groups of people meeting in their local communities, looking at the enormous power of the government or of corporations, and thinking, We don’t have a chance; there is nothing we can do. But then, at certain moments in history, these small movements join together to become larger ones. There’s a kind of vibration that moves from one to the other. This is what happened with the sit-ins in the sixties. This is how the civil-rights movement developed: with the smallest of actions taken in out-of-the-way communities—in Greensboro, North Carolina, or Albany, Georgia. And it expanded and grew until it became a force that the federal government had to recognize. And we’ve seen this again and again in history. So at the start of any movement, things look hopeless; but if you feel so hopeless that you don’t act, then those small groups will never become large ones.

Barsamian: On the fortieth anniversary of the March on Washington, Georgia Congressman John Lewis reminded people that the march had been organized without the Internet, without cellphones, without faxes, without answering machines. They’d done it just by going door-to-door and making phone calls.

Zinn: That’s an interesting point, because we tend to think that the technologies we have now are indispensable. We think, My God, what did people do? How did Tolstoy write without a computer? But human beings have enormous capabilities. It’s our nature to be ingenious and inventive, to take advantage of small openings in a controlled system and reach out and communicate with one another. So, yes, the civil-rights movement grew as a result of people doing the most basic things: going door-to-door and talking to people and holding meetings in churches. During the Vietnam War, people set up community and underground newspapers and organized teach-ins and rallies. Returning GIs would meet to share antiwar views and be encouraged by the fact that there were other GIs who opposed the war. So social movements have always been able to overcome the limits to communication. Now that we have the Internet, we have even more tools at our command.

Barsamian: In an April column in the Progressive, you write: “We are at a turning point in the history of the nation . . . and the choice will come in the ballot box.”

Zinn: Did I really say that? I’m a little embarrassed, since everyone always says they are at a turning point in history. But, clichés aside, I actually believe that today, in the United States, we are at such a crucial point. We have an administration that is more ruthless, more subject to corporate influence, more militaristic, more ambitious in its desire to seize control in all parts of the world—even in space—more dangerous than any we’ve seen in American history. It has the capacity to send its armed forces all over the world, to kill large numbers of people, to use nuclear weapons. And the members of this administration seem unconstrained by the democratic idea of listening to other voices. This is an administration that won only 47 percent of the popular vote in a tainted election and was put into office by a five-to-four vote of the Supreme Court. Yet it immediately seized 100 percent of the power and began to assert that power abroad. We have an administration that has been unrestrained in its use of power; that believes that, with ten thousand nuclear weapons and a hundred military bases worldwide, the United States is in a position to do whatever it wants. All of this makes the present moment a very important one in history.

So much hinges on the next election—and rarely do I think that very much hinges on an election. We absolutely need to defeat George Bush, because his is an especially cruel and ruthless administration. For anybody who wants to see a change in this country, beating George Bush should be a priority. It’s not that electing someone other than Bush will solve our fundamental problems, because both Democratic and Republican administrations have been aggressive in foreign policy and have had ties to corporate interests. But I think that a president who wins the election by distinguishing himself from and criticizing Bush will be under pressure from his constituency to stop the war and to stop using our enormous wealth for an inflated military budget and tax breaks for corporations, and to start using it for the needs of ordinary people.

Barsamian: We live in a country where it is easier to buy a gun than it is to vote. Why are elections on Tuesday, a workday? Why not have them on the weekend? And why do we have a winner-take-all electoral-college system, rather than one-person-one-vote majority rule?

Zinn: Those are very good questions. Why do we hold the election when people are at work? Because wage earners are the least likely to be able to take time off to vote. Corporate executives can take time off whenever they want. It’s no surprise that 50 percent of Americans don’t vote in presidential elections, and that many of them are working people.

Why do we still have the absurd system of the electoral college, which was set up in the eighteenth century? One reason is that the system is easily manipulated by powerful political groups. It creates the possibility that a minor manipulation of the popular vote can deliver all the electoral votes of a state to a single candidate. If you move your vote, for example, from 49 to 51 percent in a state, you then get 100 percent of the state’s electoral votes. It is a system that lends itself to corruption.

We saw this very blatantly in the 2000 presidential election, when Bush achieved, in a very shady way, a five-hundred-vote plurality in Florida and got all of that state’s electoral votes — enough to give him, in the opinion of five out of nine Supreme Court justices, the presidency. So we do not have a truly democratic system. We’re fooling ourselves if we think that, because we don’t have a totalitarian system or a military dictatorship, we have a real democracy with free elections. How hypocritical it is of the United States to demand that other countries have free elections, when we ourselves have elections that are not free.

Barsamian: Why aren’t our elections free?

Zinn: Too much money is involved. Money dominates the whole electoral process, with huge sums being expended by both Democrats and Republicans. Candidates need to amass enormous sums of money in order to have a chance at winning, and those sums do not come from ordinary people; they come from big-business interests. So it’s not a free election in that sense.

It’s also not a free election in the sense of people having the freedom to choose whichever candidate they want, because just two parties dominate the entire system. Other parties don’t have a chance. “Third-party” candidates are not even allowed to appear in televised presidential debates. All people can do is choose between the Democratic and Republican candidates. It’s hardly a free choice.

Barsamian: Another limit on free elections in this country is that millions of citizens who have served time in prison are denied the right to vote for the rest of their lives.

Zinn: One of the really scandalous things that happened in the 2000 election is that Florida governor Jeb Bush’s people went through the voting rolls and removed voters with criminal records from the list. Since prisoners in the United States are disproportionately people of color, it was mainly people of color who were denied the right to vote.

Barsamian: To return to the subject of literature, could you talk about Graham Greene’s The Quiet American, which was made into a film?

Zinn: It’s refreshing to find a novelist who doesn’t simply concentrate, as so many novelists do, on relationships, but who looks outside of them to what the larger society is doing and gives the reader a kind of social context. So many novels these days simply deal in a microscopic way with the romantic involvements of two or three or four people. Reading these novels, you wouldn’t know that there was anything else going on in the world. The really important novels, I think, put personal stories in a social context, as John Steinbeck’s The Grapes of Wrath and Richard Wright’s Native Son do.

The Quiet American is the story of a love triangle involving an American man, a male British journalist, and a Vietnamese woman, but it goes beyond that. The setting is Vietnam at the time when the United States was first getting involved in that country’s politics in an insidious way. The American man appears innocent but is secretly working for the U.S. government. In the guise of stopping communism, he is engaging in atrocities against civilians in Saigon. This is the social setting for the love story.

Interestingly, after the film version of the novel had been made, Miramax, a giant in the film industry, held back its release, afraid it would be considered unpatriotic in the wake of 9/11. Apparently it’s unpatriotic to suggest that the United States was doing something immoral in Vietnam. Such commentary on the morality of U.S. foreign policy is considered beyond the pale in this supposedly democratic country. It took the influence and power of the film’s star, Michael Caine, to get Miramax to finally distribute the film. I noticed, however, that the film was not given the kind of attention or advertising Miramax lavishes on many of its other films, and was consigned to a small number of art houses. Evidently, Miramax tried to limit the audience for its own film, because the film dared to make a political statement about the United States.

Barsamian: Another novel you recommend is Johnny Got His Gun, whose author, Dalton Trumbo, was persecuted in the McCarthy era. He was blacklisted, went to jail, and couldn’t find work under his own name for years. You say that your students respond positively to this novel.

Zinn: I use this book because I could give ten lectures about war, filling them with my own passionate feelings, and they would not have the impact of one evening spent reading Johnny Got His Gun.

Trumbo takes the cruelty of war to its furthest extreme, writing about a soldier who is found on the battlefield barely alive, without arms or legs, blind and deaf—really just a heart beating and a brain. This strange being, this “thing,” is picked up from the battlefield, brought to a hospital, and put on a cot. All he can do is think: about his past, his life, his small town, his girlfriend, the mayor sending him off with great ceremony to fight for democracy and liberty. At the same time that he recalls all this, he is trying to figure out how to communicate with the outside world. He can’t speak. He can’t hear. He can only sense vibrations and sunlight. He can feel the warmth of the sun and the cool of the evening. From there, he builds a calendar in his mind. He figures out a way to communicate with a nurse, who is empathetic and ingenious enough to figure out what he is doing when he taps his head against a piece of furniture. He begins to tap out messages in Morse code, and the nurse deciphers them.

The climax of the novel is when the top brass come in to give him a medal. Through the nurse, they ask him, “What do you want?” And he thinks, What do I want? Then he taps out a response. He tells them what he wants: They cannot give him back his arms, his legs, his hearing, or his sight. So he asks them to bring him into schoolhouses, churches—wherever young people and children are gathered. He says, “Point to me and say, ‘This is war.’ ”

Their response is: “This is beyond regulations.” They want him to be forgotten.

This is a story for our time. Our government wants us to forget about the GIs who come back from war blind or with missing legs and arms. No one person’s fate may be as catastrophic as that of the character in Johnny Got His Gun, but there are plenty of casualties who represent what he represents: The horrors of war.

The government, however, does not want people to be conscious of the thousands of wounded veterans in the war in Iraq. Their existence is hidden from the public. Only occasionally does a glimpse of this reality come through, as in a story that appeared in the New York Times about a young GI blinded by shell fragments in Iraq: His mother, visiting him in the hospital, passes the cots of other young people who are missing limbs. She sees a young mother back from Iraq without legs, crawling on the floor with her little child crawling behind her. This is the picture that the present administration wants to hide from the American people. A novel like Johnny Got His Gun can awaken readers both to the reality of war and to how the government seeks to hide that reality—the fact of what happens to our people and, certainly, to people on the other side.

The Sun • July 2004