By Howard Zinn

This essay, written for Z Magazine in 1990, and reprinted in my book Failure to Quit, was inspired (if you are willing to call this an inspired piece) by my students of the Eighties. I was teaching a spring and fall lecture course with four hundred students in each course (and yet with lots of discussion). I looked hard, listened closely, but did not find the apathy, the conservatism, the disregard for the plight of others, that everybody (right and left) was reporting about “the me generation.”

_____________________________________

I can understand pessimism, but I don’t believe in it. It’s not simply a matter of faith, but of historical evidence. Not overwhelming evidence, just enough to give hope, because for hope we don’t need certainty, only possibility. Which (despite all those confident statements that “history shows …” and “history proves …”) is all history can offer us.

It was on the first of February in that first year of the new decade that four Black students from North Carolina A & T College sat down at a “white” lunch counter in Greensboro, refused to move, and were arrested. In two weeks, sit-ins had spread to 15 cities in five Southern states. By the year’s end, 50,000 people had participated in demonstrations in a hundred cities, and 3,600 had been put in jail.

That was the start of the civil rights movement, which became an anti-war movement, a women’s movement, a cultural upheaval, and in its course hundreds of thousands, no, millions of people became committed for a short time, or for a lifetime. It was unprecedented, unpredicted, and for at least 15 years, uncontrollable. It would shake the country and startle the world, with consequences we are hardly aware of today.

True, those consequences did not include the end of war, exploitation, hunger, racism, military intervention, nationalism, sexism—only the end of legal racial segregation, the end of the war of Vietnam, the end of illegal abortions. It was just a beginning.

…

When activists commit civil disobedience, the degree of their distance from the general sentiment can be measured, at least roughly, by how juries of ordinary citizens react. During the war in Vietnam, when religious pacifists entered draft boards illegally to destroy draft records as a way of protesting the war, juries became increasingly reluctant to convict, and near the end of the war we saw the dramatic acquittal of the Camden 28 by a jury which then threw a party for the defendants.

Acts of civil disobedience today, at a much earlier stage of U.S. intervention, are getting verdicts of acquittal when juries are permitted to listen to the defendants’ reasons for their civil disobedience. In the spring of 1984, in Burlington, Vermont, the “Winooski 44” had occupied Senator Stafford’s office to protest his support of aid to the contras. The jury heard many hours of testimony about conditions in Nicaragua, the role of the CIA, the nature of the contras, and voted for acquittal. One of the jurors, a local house painter, said: “I was honored to be on that jury. I felt a part of history.”

In Minneapolis that same year, seven “trespassers” protesting at the Honeywell Corporation were acquitted. In 1985, men and women blocked the Great Lakes Training Station in Illinois, others blocked the South African Embassy in Chicago, nineteen people in the state of Washington halted trains carrying warheads, and all these won acquittal in court. Last year in western Massachusetts, where a protest against the CIA took place, there was another surprising acquittal. One of the jurors Donna L. Moody, told a reporter: “All the expert testimony against the CIA was alarming. It was very educational.”

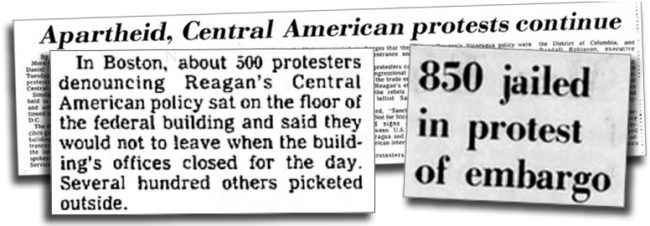

Several years ago, when Reagan announced the blockade of Nicaragua, 550 of us sat-in at the federal building in Boston to protest and were arrested. It seemed too big a group of dissidents to deal with, and charges were dropped. When I received my letter, I saw for the first time what the official complaint against all of us was: “Failure to Quit.” That is, surely, the critical fact about the continuing movement for human rights here and all over the world.

We hear many glib dismissals of today’s college students as being totally preoccupied with money and self. In fact, there is much concern among students with their economic futures—evidence of the failure of the economic system to provide for the young, more than a sign of their indifference to social injustice. But the past few years have seen political actions on campuses all over the country. For 1986 alone, a partial list shows: 182 students, calling for divestment from South Africa, arrested at the University of Texas; a black-tie dinner for alumni at Harvard called off after a protest on South African holdings; charges dropped against 49 Wellesley protesters after half the campus boycotted classes in support; and more protests recorded at Yale, Wisconsin, Louisville, San Jose, Columbia.

But what about the others, the non-protesting students? Among the liberal arts students, business majors, and ROTC cadets who sit in my classes, there are super-patriots and enthusiasts of capitalism, but also others, whose thoughts deserve some attention.

Writing in his class journal, one ROTC student, whose father was a navy flier, his brother a navy commander: “This one class made me go out and read up on South Africa. What I learned made me sick. My entire semester has been a paradox. I go to your class and I see a Vietnam vet named Joe Bangert tell of his experiences in the war. I was enthralled by his talk. By the end of that hour and a half I hated the Vietnam War as much as he did. The only problem is that three hours after that class I am marching around in my uniform … and feeling great about it. Is there something wrong with me? Am I being hypocritical? Sometimes I don’t know … ”

Young woman in ROTC, after seeing the film Hearts and Minds: “General Westmoreland said ‘Orientals don’t value lives.’ I was incredulous. And then they showed the little boy holding the picture of his father and he was crying and crying and crying .. .I must admit I started crying. What’s worse was that I was wearing my Army uniform that day and I had to make a conscious effort not to disappear in my seat.”

Young woman in the School of Management: “North broke the law, but will he be punished?… If he is let off the hook then all of America is punished. Every inner-city kid who is sent to jail for stealing food to feed his brothers and sisters is punished. Every elderly person who has to fight just to keep warm on a winter night will be punished …. The law is supposed to be on the common bond—the peace making body. Yet it only serves the function selectively—just when the people in control wish it to.”

Surely history does not start anew with each decade. The roots of one era branch and flower in subsequent eras. Human beings, writings, invisible transmitters of all kinds, carry messages across the generations. I try to be pessimistic, to keep up with some of my friends. But I think back over the decades, and look around. And then, it seems to me that the future is not certain, but it is possible.