The following is an excerpt from “Surprises,” Chapter 19 of A People’s History of the United States to highlight Native American resistance during the 1960s and 70s. As Howard Zinn states, “Never in American history had more movements for change been concentrated in so short a span of years.” This is followed by additional resources on Native American history and resistance.

By Howard Zinn • Chapter 19 in A People’s History of the United States

For a time, the disappearance or amalgamation of the Indians seemed inevitable—only 300,000 were left at the turn of the century, from the original million or more in the area of the United States. But then the population began to grow again, as if a plant left to die refused to do so, began to flourish. By 1960 there were 800,000 Indians, half on reservations, half in towns all over the country.

The autobiographies of Indians show their refusal to be absorbed by the white man’s culture. One wrote:

Oh, yes, I went to the white man’s schools. I learned to read from school books, newspapers, and the Bible. But in time I found that these were not enough. Civilized people depend too much on man-made printed pages. I turn to the Great Spirit’s book which is the whole of his creation….

A Hopi Indian named Sun Chief said:

I had learned many English words and could recite part of the Ten Commandments. I knew how to sleep on a bed, pray to Jesus, comb my hair, eat with a knife and fork, and use a toilet. … I had also learned that a person thinks with his head instead of his heart.

Chief Luther Standing Bear, in his 1933 autobiography, From the Land of the Spotted Eagle, wrote:

True, the white man brought great change. But the varied fruits of his civilization, though highly colored and inviting, are sickening and deadening. And if it be the part of civilization to maim, rob, and thwart, then what is progress? I am going to venture that the man who sat on the ground in his tipi meditating on life and its meaning, accepting—the kinship of all creatures, and acknowledging unity with the universe of things, was infusing into his being the true essence of civilization….

As the civil rights and antiwar movements developed in the 1960s, Indians were already gathering their energy for resistance, thinking about how to change their situation, beginning to organize. In 1961, five hundred tribal and urban Indian leaders met in Chicago. Out of this came another gathering of university-educated young Indians who formed the National Indian Youth Council. Mel Thorn, a Paiute Indian, their first president, wrote:

There is increased activity over on the Indian side. There are disagreements, laughing, singing, outbursts of anger, and occasionally some planning…. Indians are gaining confidence and courage that their cause is right.The struggle goes on…. Indians are gathering together to deliberate their destiny….

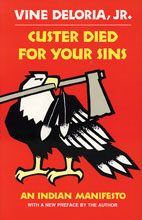

Around this time, Indians began to approach the United States government on an embarrassing topic: treaties. In his widely read 1969 book, Custer Died for Your Sins, Vine Deloria, Jr., noted that President Lyndon Johnson talked about America’s “commitments,” and President Nixon talked about Russia’s failure to respect treaties. He said: “Indian people laugh themselves sick when they hear these statements.”

The United States government had signed more than four hundred treaties with Indians and violated every single one. For instance, back in George Washington’s administration, a treaty was signed with the Iroquois of New York: “The United States acknowledge all the land within the aforementioned boundaries to be the property of the Seneka nation….” But in the early sixties, under President Kennedy, the United States ignored the treaty and built a dam on this land, flooding most of the Seneca reservation.

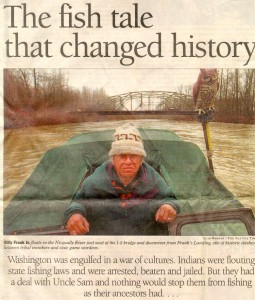

Resistance was already taking shape in various parts of the country. In the state of Washington, there was an old treaty taking land from the Indians but leaving them fishing rights. This became unpopular as the white population grew and wanted the fishing areas exclusively for themselves. When state courts closed river areas to Indian fishermen, in 1964, Indians had “fish-ins” on the Nisqually River, in defiance of the court orders, and went to jail, hoping to publicize their protest.

Resistance was already taking shape in various parts of the country. In the state of Washington, there was an old treaty taking land from the Indians but leaving them fishing rights. This became unpopular as the white population grew and wanted the fishing areas exclusively for themselves. When state courts closed river areas to Indian fishermen, in 1964, Indians had “fish-ins” on the Nisqually River, in defiance of the court orders, and went to jail, hoping to publicize their protest.

A local judge the following year ruled that the Puyallup tribe did not exist, and its members could not fish on the river named for them, the Puyallup River. Policemen raided Indian fishing groups, destroyed boats, slashed nets, manhandled people, arrested seven Indians. A Supreme Court ruling in 1968 confirmed Indian rights under the treaty but said a state could “regulate all fishing” if it did not discriminate against Indians. The state continued to get injunctions and to arrest Indians fishing. They were doing to the Supreme Court ruling what whites in the South had done with the Fourteenth Amendment for many years—ignoring it. Protests, raids, arrests, continued into the early seventies.

Some of the Indians involved in the fish-ins were veterans of the Vietnam war. One was Sid Mills, who was arrested in a fish-in at Frank’s Landing on the Nisqually River in Washington on October 13, 1968. He made a statement:

I am a Yakima and Cherokee Indian, and a man. For two years and four months, I’ve been a soldier in the United States Army. I served in combat in Vietnam-until critically wounded…. I hereby renounce further obligation in service or duty to the United States Army.My first obligation now lies with the Indian People fighting for the lawful Treaty to fish in usual and accustomed water of the Nisqualiy, Columbia and other rivers of the Pacific Northwest, and in serving them in this fight in any way possible….

My decision is influenced by the fact that we have already buried Indian fishermen returned dead from Vietnam, while Indian fishermen live here without protection and under steady attack… .

Just three years ago today, on October 13, 1965, 19 women and children were brutalized by more than 45 armed agents of the State of Washington at Frank’s Landing on the Nisqually river in a vicious, unwarranted attack….

Interestingly, the oldest human skeletal remains ever found in the Western Hemisphere were recently uncovered on the banks of the Columbia River—the remains of Indian fishermen. What kind of government or society would spend millions of dollars to pick upon our bones, restore our ancestral life patterns, and protect our ancient remains from damage-while at the same time eating upon the flesh of our living People…?

We will fight for our rights.

Indians fought back not only with physical resistance, but also with the artifacts of white culture—books, words, newspapers. In 1968, members of the Mohawk Nation at Akwesasne, on the St. Lawrence River between the United States and Canada, began a remarkable newspaper, Akwesasne Notes, with news, editorials, poetry, all flaming with the spirit of defiance. Mixed in with all that was an irrepressible humor. Vine Deloria, Jr., wrote:

Every now and then I am impressed with the thinking of the non-Indian. I was in Cleveland last year and got to talking with a non-Indian about American history. He said that he was really sorry about what had happened to Indians, but that there was a good reason for it. The continent had to be developed and he felt that Indians had stood in the way, and thus had had to be removed. “After all,” he remarked, “what did you do with the land when you had it?” I didn’t understand him until later when I discovered that the Cuyahoga River running through Cleveland is inflammable. So many combustible pollutants are dumped into the river that the inhabitants have to take special precautions during the summer to avoid setting it on fire. After reviewing the argument of my non- Indian friend I decided that he was probably correct. Whites had made better use of the land. How many Indians could have thought of creating an inflammable river?

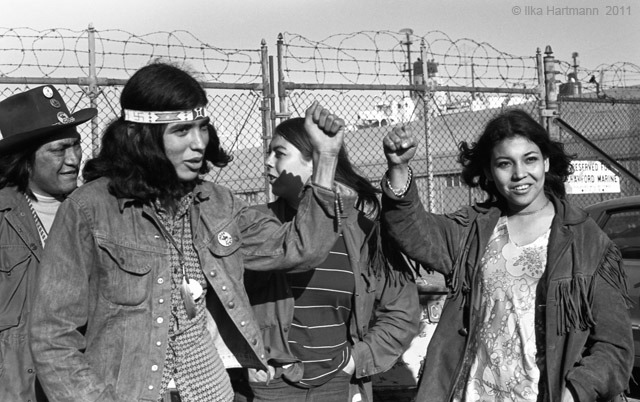

In 1969, November 9, there took place a dramatic event which focused attention on Indian grievances as nothing else had. It burst through the invisibility of previous local Indian protests and declared to the entire world that the Indians still lived and would fight for their rights. On that day, before dawn, seventy-eight Indians landed on Alcatraz Island in San Francisco Bay and occupied the island. Alcatraz was an abandoned federal prison, a hated and terrible place nicknamed “The Rock.” In 1964 some young Indians had occupied it to establish an Indian university, but they were driven off and there was no publicity.

This time, it was different. The group was led by Richard Oakes, a Mohawk who directed Indian Studies at San Francisco State College, and Grace Thorpe, a Sac and Fox Indian, daughter of Jim Thorpe, the famous Indian college football star and Olympic runner, jumper, hurdler. More Indians landed, and by the end of November nearly six hundred of them, representing more than fifty tribes, were living on Alcatraz. They called themselves “Indians of All Tribes” and issued a proclamation, “We Hold the Rock.” In it they offered to buy Alcatraz in glass beads and red cloth, the price paid Indians for Manhattan Island over three hundred years earlier. They said:

We feel that this so-called Alcatraz Island is more than suitable for an Indian reservation, as determined by the white man’s own standards. By this we mean that this place resembles most Indian reservations in that:

- It is isolated from modern facilities, and without adequate means of transportation.

- It has no fresh running water.

- It has inadequate sanitation facilities.

- There are no oil or mineral rights.

- There is no industry and so unemployment is very great.

- There are no health care facilities.

- The soil is rocky and non-productive; and the land does not support game.

- There are no educational facilities.

- The population has always exceeded the land base.

- The population has always been held as prisoners and dependent upon others.

They announced they would make the island a center for Native American Studies for Ecology: “We will work to de-pollute the air and waters of the Bay Area…restore fish and animal life….”

In the months that followed, the government cut off telephones, electricity, and water to Alcatraz Island. Many of the Indians had to leave, but others insisted on staying. A year later they were still there, and they sent out a message to “our brothers and sisters of all races and tongues upon our Earth Mother”:

We are still holding the Island of Alcatraz in the true names of Freedom, Justice and Equality, because you, our brothers and sisters of this earth, have lent support to our just cause. We reach out our hands and hearts and send spirit messages to each and every one of you—WE HOLD THE ROCK…. We have learned that violence breeds only more violence and we therefore have carried on our occupation of Alcatraz in a peaceful manner, hoping that the government of these United States will also act accordingly….

We are a proud people! We are Indians! We have observed and rejected much of what so-called civilization offers. We are Indians! We will preserve our traditions and ways of life by educating our own children. We are Indians! We will join hands in a unity never before put into practice. We are Indians! Our Earth Mother awaits our voices.

We are indians Of All Tribes! WE HOLD THE ROCK!

Six months later, federal forces invaded the island and physically removed the Indians living there.

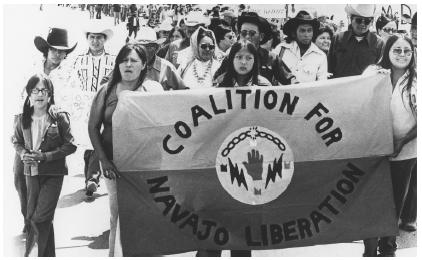

It had been thought that the Navajo Indians would not be heard from again. In the mid-1800s, United States troops under “Kit” Carson burned Navajo villages, destroyed their crops and orchards, forced them from their lands. But in the Black Mesa of New Mexico they never surrendered. In the late 1960s, the Peabody Coal Company began strip mining on their land—a ruthless excavation of the topsoil. The company pointed to a “contract” signed with some Navajos. It was reminiscent of the “treaties” signed with some Indians in the past that took away all Indian land.

One hundred and fifty Navajos met in the spring of 1969 to declare that the strip mining would pollute the water and the air, destroy the grazing land for livestock, use up their scarce water resources. A young woman pointed to a public relations pamphlet put out by the Peabody Coal Company, showing fishing lakes, grassland, trees, and said: “We’re not going to have anything like those you see in the pictures…. What is the future going to be like for our children, our children’s children?” An elderly Navajo woman, one of the organizers of the meeting, said, “Peabody’s monsters are digging up the heart of our mother earth, our sacred mountain, and we also feel the pains…. I have lived here for years and I’m not about to move.”

The Hopi Indians were also affected by the Peabody operations. They wrote to President Nixon in protest:

Today the sacred lands where the Hopi live are being desecrated by men who seek coal and water from our soil that they may create more power for the whiteman’s cities.. . . The Great Spirit said not to allow this to happen…. The Great Spirit said not to take from the Earth-not to destroy living things…. It is said by the Great Spirit that if a gourd of ashes is dropped upon the Earth, that many men will die and that the end of this way of life is near at hand. We interpret this as the dropping of atomic bombs on Hiroshima and Nagasaki. We do not want to see this happen to any place or any nation again, but instead we should turn all this energy for peaceful uses, not for war….

In the fall of 1970, a magazine called La Raza, one of the countless local publications coming out of the movements of those years to supply information ignored in the regular media, told about the Pit River Indians of northern California. Sixty Pit Indians occupied land they said belonged to them; they defied the Forest Services when ordered to leave. One of them, Darryl B. Wilson, later recalled: “As the flames danced orange making the trees come to life, and the cold creeped out of the darkness to challenge the speaking fire, and our breath came in small clouds, we spoke.” They asked the government by what treaty it claimed the land. It could point to none. They cited a federal statute (25 USCA 194) that where there was a land dispute between Indian and white “the burden of proof falls on the white man.”

They had built a quonset hut, and the marshals told them it was ugly and ruined the landscape. Wilson wrote later:

The whole world is rotting. The water is poisoned, the air polluted, the politics deformed, the land gutted, the forest pillaged, the shores ruined, the towns burned, the lives of the people destroyed…. and the federals spent the best part of October trying to tell us the quonset hut was “ugly”! To us it was beautiful. It was the beginning of our school. The meeting place. Home for our homeless. A sanctuary for those needing rest. Our church. Our headquarters. Our business office. Our symbol of approaching freedom. And it still stands.

It was also the center for the reviving of our stricken, diluted and separated culture. Our beginning. It was our sun rising on a clear spring day when the sky holds no clouds. It was a good and pure thing for our heart to look upon. That small place on earth. Our place.

But 150 marshals came, with machine guns, shotguns, rifles, pistols, riot sticks, Mace, dogs, chains, manacles. “The old people were frightened. The young questioned bravery. The small children were like a deer that has been shot by the thunder stick. Hearts beat fast as though a race was just run in the heat of summer.” The marshals began swinging their riot sacks, and blood started flowing. Wilson grabbed one marshal’s club, was thrown down, manacled, and while lying face down on the ground was struck behind the head several times. A sixty-six-year-old man was beaten into unconsciousness. A white reporter was arrested, his wife beaten. They were all thrown into trucks and taken away, charged with assaulting state and federal officers and cutting trees—but not with trespassing, which might have brought into question the ownership of the land. When the episode was all over, they were still defiant.

Indians who had been in the Vietnam war made connections. At the “Winter Soldier Investigations” in Detroit, where Vietnam veterans testified about their experiences, an Oklahoma Indian named Evan Haney told about his:

The same massacres happened to the Indians 100 years ago. Germ warfare was used then. They put smallpox in the Indians’ blankets…. I got to know the Vietnamese people and I learned they were just like us…. What we are doing is destroying ourselves and the world.

I have grown up with racism all my life. When I was a child, watching cowboys and Indians on TV I would root for the cavalry, not the Indians. It was that bad. I was that far toward my own destruction….

Though 50 percent of the children at the country school I attended in Oklahoma were Indians, nothing in school, on television, or on the radio taught anything about Indian culture. There were no books on Indian history, not even in the library….

But I knew something was wrong. I started reading and learning my own culture….

I saw the Indian people at their happiest when they went to Alcatraz or to Washington to defend their fishing rights. They at last felt like human beings.

Indians began to do something about their “own destruction”—the annihilation of their culture. In 1969, at the First Convocation of American Indian Scholars, Indians spoke indignantly of either the ignoring or the insulting of Indians in textbooks given to little children all over the United States. That year the Indian Historian Press was founded. It evaluated four hundred textbooks in elementary and secondary schools and found that not one of them gave an accurate depiction of the Indian.

A counterattack began in the schools. In early 1971, forty-five Indian students at Copper Valley School, in Glennalen, Alaska, wrote a letter to their Congressman opposing the Alaska oil pipeline as ruinous to the ecology, a threat to the “peace, quiet and security of our Alaska.”

Other Americans were beginning to pay attention, to rethink their own learning. The first motion pictures attempting to redress the history of the Indian appeared: one was Little Big Man, based on a novel by Thomas Berger. More and more books appeared on Indian history, until a whole new literature came into existence. Teachers became sensitive to the old stereotypes, threw away the old textbooks, started using new material. In the spring of 1977 a teacher named Jane Califf, in the New York City elementary schools, told of her experiences with fourth and fifth grade students. She brought into class the traditional textbooks and asked the students to locate the stereotypes in them. She read aloud from Native American writers and articles from Akwesasne Notes, and put protest posters around the room. The children then wrote letters to the editors of the books they had read:

Dear Editor,

I don’t like your book called The Cruise of Christopher Columbus. I didn’t like it because you said some things about Indians that weren’t true. . . . Another thing I didn’t like was on page 69, it says that Christopher Columbus invited the Indians to Spain, but what really happened was that he stole them!

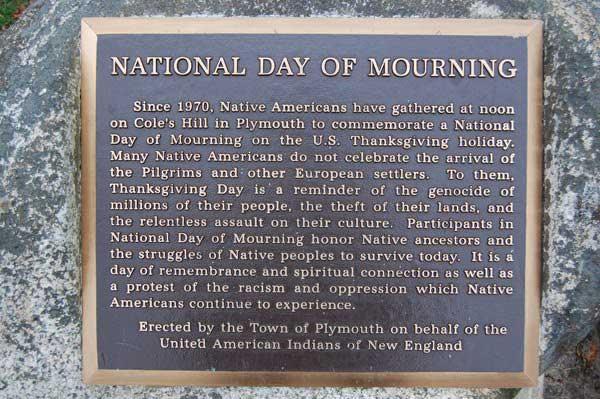

On Thanksgiving Day 1970, at the annual celebration of the landing of the Pilgrims, the authorities decided to do something different: invite an Indian to make the celebratory speech. They found a Wampanoag Indian named Frank James and asked him to speak. But when they saw the speech he was about to deliver, they decided they did not want it. His speech, not heard at Plymouth, Massachusetts, on that occasion, said, in part (the whole speech is in Chronicles of American Indian Protest):

I speak to you as a Man-a Wampanoag Man….It is with mixed emotions that I stand here to share my thoughts….The Pilgrims had hardly explored the shores of Cape Cod four days before they had robbed the graves of my ancestors, and stolen their corn, wheat, and beans….Our spirit refuses to die. Yesterday we walked the woodland paths and sandy trails. Today we must walk the macadam highways and roads. We are uniting. We’re standing not in our wigwams but in your concrete tent. We stand tall and proud and before too many moons pass we’ll right the wrongs we have allowed to happen to us….

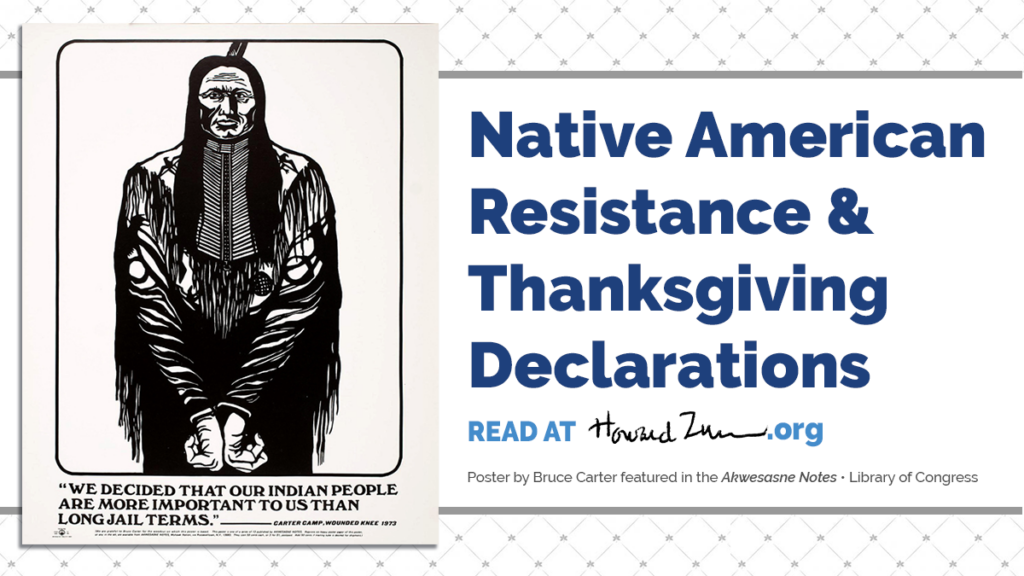

Image: Poster by Bruce Carter featured in the Akwesasne Notes • Library of Congress

Image: Alcatraz Island Occupiers • By Ilka Hartmann

Image: Coalition of Navajos • Everyculture.com

Image: Photo of Frank James • Many Hoops Around Thanksgiving

More on Native American Resistance and Struggle

Native American Activism: 1960s to Present

A collection of recent Native movements and activists who have continued to struggle for sovereignty, dignity, and justice for their communities. Continue reading at the Zinn Education Project.

Abolish Columbus Day Campaign

Information and resources to join the campaign to Abolish Columbus Day. Encourages schools to petition their administration and for communities to introduce legislation to rename Columbus Day to Indigenous Peoples Day. Below is . Read more at the Zinn Education Project.

Teaching Resources on Native Americans

Visit the the Zinn Education Project for resources on Native Americans.

Native American Activism: 1960s to Present

Q’Orianka Kilcher reads Chief Joseph’s 1879 speech. Recorded, February 1, 2007, at All Saints Church, Pasadena, CA. Watch at The People Speak on Vimeo.com.

Tecumseh's Speech to the Osages (Winter 1811-1812)

Deepa Fernandes reads Tecumseh’s speech on March 10, 2007, at The Great Hall at Cooper Union, New York, NY. Watch at The People Speak on Vimeo.com.

Category: Tags: Excerpts