Patricia Marx Interviews Howard Zinn | WNYC Radio

Recorded in the 1960s (estimate 1964-1965 based on transcript), Patricia Marx sits down with historian Howard Zinn to discuss his books, SNCC: The New Abolitionists and The Southern Mystique. Zinn describes his experiences teaching at Spelman College in Atlanta, Georgia, from 1956 to 1963, and his subsequent observations on racial prejudice in the southern United States.

Patricia Marx was a nationally syndicated reporter for public radio and conducted interviews for WNYC with people such as Dick Gregory and Lorraine Hansberry. In 1970, she married Daniel Ellsberg and changed her name to Patricia Ellsberg. She is a social change advocate with decades of experience in the peace and energy movements and often speaks with her husband at anti-war and anti-nuclear events. [Bio adapted from PBS.org]

Published by The NYPR Archive Collections.

Transcript

This transcript was generated by Open Transcript Editor Pilot and copyedited by the Howard Zinn website staff.

PATRICIA MARX (PM): I’m delighted to have as my guest today Professor Howard Zinn who recently spent seven years as chairman of the history department at Spelman College which is a predominantly Negro school in Atlanta, Georgia. During this time professor Zinn observed and participated in the civil rights struggle, and has just written two books out of his personal experience.

One entitled The New Abolitionists is about the activists civil rights group the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee. The other entitled The Southern Mystique challenges our accepted views of the South and race prejudice. Mr. Zinn, just what you mean by the Southern mystique?

HOWARD ZINN (HZ): There’s a certain atmosphere built up around the South in our history books, I guess, in our literature, in the folklore of the nation. And this indefinable feeling about the South somehow was one of mystery, and that people somehow had gotten the notion through this long tradition of literature and history and folklore that the South was an unfathomable quantity, that it was so different from the rest of the nation, that there was no point in attempting to penetrate this mystery. And as I observed the actions and the ideas in action of white Southerners and negro Southerners about me, I began to realize that the South was very much like the rest of the nation. That it was not unfathomable, not mysterious, not indecipherable, that it was subject to rational consideration and analysis and thought. That something like race prejudice, for instance, which so many—not only American Northerners but perhaps people all over the world have begun to think is something ingrained and mysterious in the Southern white—that this race prejudice is really something understandable, and something with which you can grapple, and something you can change.

PM: Mr. Zinn, isn’t it really the known—such as lynchings and forced segregation, murders—isn’t what we know about the South that makes us feel race prejudice is unfathomable and unchangeable?

HZ: Well these are the facts, and these are true, that is the mystery as I think all mysteries. The mystery is based on an element of truth. The South has been more violent, has been more prejudiced, has reacted in the most terrifying ways to Negroes, has killed the most Negroes, and brutalized them more than any other section of the nation. This is true. What is not true, however, is the idea that this therefore is an unchangeable part of the South. That this has always been in the South and will always be there, and nothing we can do will erase this feeling in the minds of white Southerners in this pattern of action that they have had through the history.

PM: It’s often said that one must wait to change men’s hearts before one changes their laws. Do you agree with this?

HZ: I think this is one of the fundamental points in The Southern Mystique and I suppose one of the reasons I set out to write it. Because Americans concerned with the race problem, I think particularly liberal Americans, have long said, “Well the way to get at the problem is to change first the thinking of men, the feelings of man,” mainly by education—which meant mainly by verbal education—and then this would have an effect on the situation in the South. And what I began to see living in Atlanta, through seven years of very intense change, those, exactly those seven years in which the South has been going through this great turmoil—from 1956, two years after the Supreme Court decision to 1963—and what I saw in these seven years was that white Southerners began to change their patterns of behavior before they changed their way of thinking, and they did this because several things happened. Because one, the laws of the community changed, and second, the atmosphere in the community—that which is created by the predominant opinion of editors, ministers, professors, and all of the powerful organs of opinion in the community, all of these things began to create a different atmosphere, and it was this changed atmosphere— not some internal change in the way of thinking—this changed atmosphere and the changed legal situation which led them to change their behavior even before they changed their minds, and my argument is that what you really do is first change the way people behave by creating a new environment around them. And as they begin to behave differently, they begin to think differently. And this is based, I suppose, on the idea that people’s behavior does not come as much out of some internalized thought process as it does out of the behavior they see about them, whether this is consistent with their internal thinking or not. That is, so many people go through life behaving in a way that they don’t think they should behave simply because this, these are the laws of society, and these are the patterns and the mores and I’m saying you change the mores, you change the environment of the white Southern, you change the way he behaves, and then you change his way of thinking.

PM: What are means you change the way he behaves. Is it strictly through law?

HZ: Not strictly but this is one way. I think at one point in the book I mention this incident on the bus which a student of mine experienced. This was a class and I suppose we weren’t supposed to be discussing this in class but you know, we teachers get off on things and students get off on things, and I was happy to let it get off this way. She told about an incident that happened that morning and was the morning after the busses had been legally desegregated in the federal courthouse in Atlanta. This is a Negro girl, a student of mine, and she’d gotten on the bus and she saw a Negro man sitting in the front of the bus—the very first morning after the court had said now it is legal for Negroes to sit in front of the bus. And then a white woman got onto the bus saw this Negro man sitting in the front, asked him to move, he wouldn’t move, he said, “Well, you know, don’t read the newspapers?”— very quietly. And then she appealed to the bus driver, a white Southern bus driver who, well, whose feelings on race you can well imagine mirrored those of the community and of tradition. And the bus driver wouldn’t do anything. He called the policeman because she insisted, and the policeman got on, and when the white woman asked the policeman to remove the Negro man, the policeman turned to the woman, and said to her, very quietly, “Ma’am, don’t you read the newspapers?” In other words, the white policeman, the white bus driver, both of them undoubtedly in their minds segregationists, were immediately, within 24 hours, conforming to a judgment of the court, whether they liked it or not. And what this meant was that from this point on Negroes and whites would be sitting, not fully integrated, but at least partly integrated, and occasionally integrated in the buses. And little white children growing up in Atlanta and seeing occasionally Negro sitting next to whites on the buses would think differently than did their forebears, their fathers and their grandfathers who grew up always seeing whites and Negroes sitting in their places. The thinking will change now.

PM: But does that mean that there are things that are more important to the Southernern other than segregation?

HZ: I think this is, this is precisely the point. That all of us, and the white Southerner is like all of us—this to me is very important consideration—he’s a human being as we all are, and I think we all have a certain set of values which are arranged in a kind of hierarchy. Some are more important than others. And for the white Southerner, and this sort of crashed in on me one day on one month while I was in the South. The white southerner has always valued segregation., but never or almost never more than other things which mean more to him. When the white Southerner confronted with a choice between losing his cherished racial traditions and losing something which he values even more, it may be his freedom, it may be something economic, it may be the good opinion of the community, but when he faces a choice between those he will give up racism.

PM: Mr. Zinn, you’ve been speaking about Atlanta, your experience in Atlanta, which is considered a model city of race relations, and I wonder whether this experience would apply to the Deep South, the rest of the Deep South, which is known for its violent reaction to integration?

HZ: It doesn’t apply as quickly, and it doesn’t apply as fully, but I think it applies in time. I left Atlanta in winter of 1961 to go into Albany, Georgia, which is as different from Atlanta as Mississippi is from Massachusetts. This is the hardcore slave plantation South. And there I saw the kind of South you’re talking about, the South of lynchings where really the odor of slavery still lingers and Albany at that time looked as if it would never become another Atlanta, but today it is moving in that direction. The library has been desegregated in Albany, the bus stops and the train stations have been desegregated, the schools have begun to be desegregated, a Negro has run for Congress in Albany, Georgia—he didn’t win, but he got votes and he will get more votes. There’s a slightly different atmosphere in Albany, Georgia, today. I’ve been in Mississippi and in Alabama, and some of those places, most of those places today, still remain intransigent. In fact, they look today like Atlanta looked 8 years ago. But Jackson, Mississippi, a few months ago, and you know, Mississippi is the worst. In Jackson, Mississippi, a few months ago, saw the peaceful admission of Negro children to white schools in a number of communities throughout the state. And what this meant was that the police chief, the mayor, and certain citizens of those communities decided that peace was more important than segregation. And so they saw trouble coming—they knew what had happened at Little Rock and at other places where the South had put up resistance to the desegregation of schools and had lost in the end, and they decided we must give in. And because they are giving in, because they are—they haven’t changed their minds but they’re changing their behavior—because of this, little white children in Jackson, Mississippi, will go to school with a little Negro children for the first time, and I think they’ll grow up different.

PM:How effective has the civil rights movement, the activist groups, been in promoting the cause of equality?

HZ: Well they are the critical element in the situation because the courts alone can only issue decrees. Congress alone can only pass laws. If the civil rights movement had not gotten into the streets, starting with the Montgomery Bus Boycott and then moving into the sit-ins of 1960 and the Freedom Rides of 1961 and the street demonstrations in Albany in ’62 and the great, great thrusts of energy by mass movements of Negroes in the streets of Birmingham and Jackson, everywhere else in the South in ‘63—if all of this had not taken place, then the civil rights laws passed by Congress, the decisions made by the Supreme Court would have remained as dead as the 14th Amendment did from 1870 to 1954. The civil rights movements, the and this means mainly the Negro people in the South, they really have given the force behind whatever legal decisions are made by the government.

PM: Isn’t there in the South an element in the Negro population that is much more conservative than you would be or the activists would be? And isn’t this a force that you have to combat also?

HZ: There is, and there are conservative Negroes. I know because I lived among them. I lived on a Negro college campus and Negro schoolteachers, and Negro college professors, and Negro college presidents and Negro businessmen, and Negro insurance men have sometimes managed to carve out a certain way of life for themselves, even in the segregated South, which protects them from the worst excesses of the system and which makes them complacent. Not all of them but many of them. But what has been interesting is the way these conservatives, Negro conservatives in the South, have in the face of this great outpouring of militancy by young Negroes all around them, these conservatives have had to keep quiet. And today a Negro is called conservative when he is simply not as radical as the, what are called the extreme groups, the very militant groups.

PM: Did you find it difficult being more radical yourself to work with a more establishment administration at Spelman College?

HZ: I found it difficult and I found it marvelous. I found it difficult because, yes, I irritated, I’m sure, my college president and deans and the deans of women and some of the teachers and some of the more conservative elements in the community just as I probably irritated white segregationist leaders in the Atlanta community. But on the other hand, the students themselves, who were the heart of this movement, my own students and other students who went into the restaurants and sat in, who marched downtown in the face of helmeted state troopers guarding the state capitol against their entrance, well these students were so happy that they could find a college professor, or two or three of four, who would go with them, who would march with them, who would sit with them, that this made up for everything.

PM: Was the treatment that they received in the jails, is that a very brutal kind of treatment?

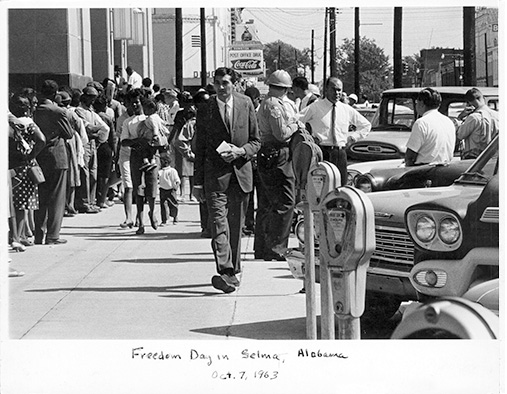

HZ: This…It’s a hard thing to talk about. I’ll tell you why. It’s like asking was slavery brutal. And, after all not all slaves were whipped, and maybe only some slaves were whipped, and most of them were just slaves. There are some institutions which are brutal in themselves, just in the ordinary day-to-day living out of that institution, and being in jail—anywhere—is brutal simply because you’re deprived of your freedom. And I guess what is most damaging is the thought that you’re there unjustly. But Southern jails, and Southern jails in the Deep South—in Albany, Georgia, in Selma, Alabama, in Jackson, Mississippi, in McComb and Hattiesburg, and in these other hardcore areas of the South—these are unspeakable. There the jailers are brutes, there you are, people are beaten. Well, just, well it was just almost exactly a year ago that I walked into a jailhouse in Hattiesburg, Mississippi, to bail out a young white SNCC worker—that is a worker of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee, a young recent graduate of Yale Law School who decided not to go into corporate law on Wall Street but to go into Mississippi and work with the movement—and he went to jail because he was picked up, as so many civil rights workers are picked up, on false traffic charges and kept in jail overnight. And I came to take him out of jail and he came down the corridor, blood all over him, on his shirt, on his pants, his nose looked as if it were broken, his face was gashed, he had been given a working over in the jail the night before and spent the night in a semi-senseless and bleeding condition. And this has happened so many, so many times in Southern jails. And what is the most terrible thing about it is this is happened in a federal government where the national administration has all the legal and actual power to prevent this but has not moved to prevent this.

PM: You spoke quite critically of the federal government in not doing what it could do. I wonder if you would talk about that a little bit.

HZ: There’s been a great deal of misinformation, misinformation to a great extent spread by the federal government itself about its own role in the South. Let’s take the murder of the three young civil rights workers in Mississippi last June, June 21. This could have been prevented if the federal government had acted with the power that it has legally. But for years now, and by for years I mean ever since the civil rights movement began in earnest with the sit-ins in 1960, brutality and murder have taken place in the South with the federal government keeping out of it and maintaining that it was not within its power to do anything about the situation. In actuality there are number of laws on the statute books of the United States government which make it a federal offense for any person to deprive any other person of his constitutional rights. What this means is that anybody who does this is violating a federal law. What this means, also, is that any federal agent, an F.B.I. agent, for instance or another agent, can arrest such a person for violating such a law. But in instance after instance, federal agents, members of the F.B.I., stood by and watched people being beaten or watched people being taken away to jail and didn’t do a thing about it, didn’t step in, didn’t make an arrest, didn’t act according to federal law. The reason, of course, is a political one. That the federal government throughout its history, and even today, plays a cautious role. To the rest of the world it seems as if the federal government plays a very active role, they see the civil rights bill of ‘57 passed, and the civil rights law of 1960, and civil rights law in 1964, and they don’t see how much sweat and agony, how much marching and parading and how many beatings and how many murders went into that bill that finally emerged. And then they don’t see how difficult it is to get the federal government to enforce these laws once they are passed.

PM: What do you think can be done by the citizens of the nation to activate this federal government?

HZ: One thing they might do is to simply let it be known in some way to their congressman, to the president, to the Department of Justice, publicly in newspapers and letters to the newspapers, with every power that words can give them. Let it be known that they know that the federal government can act according to law to send a protective force of federal agents into the deep South wherever civil rights are being violated, and to prevent murders before they begin to take place. There is a law on the books, passed a very long time ago—section 333, Title 10 of the United States Code—and this law says that whenever any state is unable or fails or is unwilling to protect the constitutional rights of any citizen of that state, then the president may use any means he wishes to protect those rights. This means not only that the president can send troops, which I at this point am not urging, but it means that the federal, that the president, if he wants to, can create, for instance, a special force of federal agents. Preferably not the F.B.I. because they’re not enthusiastic about civil rights. A special force of federal agents which will be stationed at trouble points in the South, and which will act to protect civil rights workers and Negroes from violence and from deprivation of their rights, and which will act simply as a protective force, as a screen. As soon as this is set up I would estimate that the situation will begin to change radically. Deputy sheriffs and sheriffs will not behave with the brutality that they have behaved. They have behaved this way because they felt immune, and because they’ve been immune. It’s time to take away this immunity.

PM: Mr. Zinn, whether you call them troops or agents, would this in effect be setting up a federal police state in the South?

HZ: No, it wouldn’t be setting up a federal police state. What it would be doing would be to set up a branch of the federal government which enforces one part of federal law in the same way that federal revenue agents enforce fiscal law, and in the same way that F.B.I. agents enforce laws against interstate kidnapping, interstate auto theft, embezzlement, use of the mails to defraud, and so on. You see, we have federal laws in the South which federal agents, right now enforce, acting as federal policeman. But the one kind of law which has remained immune from enforcement in the South has been civil rights law. And all that I’m suggesting is that civil rights laws be placed on the same footing as all other laws. That a sheriff who drags a civil rights worker into jail and beats him be treated as a bank robber is treated who is immediately apprehended by the F.B.I. and thrown into the federal penitentiary to go through the judicial process.

PM: Mr. Zinn, you’ve been talking about both the progress and the deep-rooted violence. What is your forecast, say, in 10 years, what will the progress be in terms of race relations?

HZ: Oh, I think…I don’t…it’s hard to forecast. I hesitate to forecast for this reason….because too many of us, and I include myself here, forecast from a standpoint of passivity. That is we want to stand by and watch how things develop, and I think the only reasonable forecast that can be made is one that’s based on action. I think if we forecast from the standpoint of acting ourselves, then we can predict that very good and positive, favorable things are going to take place in the South in the area of race relations in the next 10 years.

PM: What short of going down and being a SNCC worker or a professor of history at Spelman College, what can a responsible individual do, without changing the whole pattern of his life?

HZ: Well without changing the whole pattern of his life, of course, is an important phrase. It would be good if we could change the patterns of our lives, so many people have. I mean reshaping your life in terms of what you see about you for the first time, and what you spend your spare time doing, and the fact that you become aware, perhaps, of the Negro community where you live in a way that you never were before. Because Negroes are invisible wherever they live, in the North and in the South, and it’s interesting that white Northerners see Negroes in Mississippi now in the headlines before they see the Negroes living around the corner. And to become aware of this, to become aware of the little Mississippian corners of our own community, I think this would be a very great contribution.

PM: And then what?

HZ: To organize. To act. To pretend that we are the government. It doesn’t mean that, well, we are supposed to be, of course, in a democracy, but to do those things which we want the government to do, and which we want other people to do, and by example, therefore, to lead both the government and other groups of people to act in the same way. To set up, perhaps, parallel institutions where existing institutions don’t do what we want. The Freedom School idea, for instance, a marvelous idea, to set up a school in a community where you bring Negroes and whites together in a way that they are not brought together in the ordinary school. To create little yardsticks, as the T.V.A. was to the power industry. Little examples in schools, in housing, in social life, in every way we can. To begin to break out of the professional specializations in which we are all involved and to become human beings first, and lawyers second, teachers second, journalists second.

PM: Mr. Zinn, I would thank you for this interview. You’ve been listening to Professor Howard Zinn, author of The Southern Mystique. Thank you and goodbye for now.