December 30 is the anniversary of Daniel Ellsberg and Anthony Russo being indicted in 1971 for releasing the Pentagon Papers. The papers were part of a 7,000-page, top secret history of the U.S. political and military involvement in the Vietnam War from 1945-71. In other words, their “crime” was to make the American public aware of the history of the war.

Excerpted from chapter 12 of You Can’t Be Neutral on a Moving Train, Howard Zinn recounts the lead-up to Ellsberg and Russo’s indictment. Following are resources for learning more about the Pentagon Papers, Vietnam, and Anti-War Movements.

By Howard Zinn

That same year, 1973, I was called to Los Angeles to testify in another trial connected with the war — the Pentagon Papers trial of Daniel Ellsberg and Anthony Russo.

I had met Dan Ellsberg four years earlier, when we spoke from the same platform at an antiwar meeting. Noam Chomsky had told me about him: “an interesting man.” Ellsberg had a doctorate from Harvard in economics, had been in the Marines, in the State Department and the Defense Department. He had gone to Vietnam, and what he’d seen there had turned him against the war. He was now a research fellow at M.I.T.

Over the next months, he and I and his wife, Pat, and Roz became friends. One evening when the four of us were having coffee in their Cambridge apartment near Harvard Square, Dan said he had to tell us something in strict confidence. When he’d been with the Rand Corporation, a “think tank” for the Defense Department, he had helped put together a secret report, an official history of the Vietnam War.

Going over the internal documents, it was clear to him that the United States had lied again and again to the American people. He decided that the papers constituted a history that the public had a right to know. As one of the top scholars on the project, he was given clearance to take them home. He enlisted the aid of a friend, former Rand researcher Anthony Russo, in a bold plan to photocopy and release to the public all seven thousand pages, each of which was stamped “Top Secret.”

They found a friend who ran an advertising agency and had a copying machine. After the agency closed up shop at five, Dan and Tony went to work, making multiple copies of what became known as the Pentagon Papers. Sometimes Dan’s teenage kids, Robert and Mary, would help, methodically crossing out the words “Top Secret” on every page.

They worked late into the night (this was the fall of 1969) for weeks. Once, after midnight, a policeman, seeing the office lighted, came upstairs. They explained, “We’re doing some photocopying.” He left.

Copies of the Pentagon Papers were then sent to certain senators and members of Congress known to be against the Vietnam War, asking them to publicize the document. None of them would do it. The idea of “classified information,” the words “Top Secret,” had become something sacred in the almost hysterical atmosphere of the Cold War, and now, in a real war.

“Would you be interested in seeing some of the papers?” Dan asked. He went to a closet and gave me a pile of documents. For the next several weeks I kept them in my office, out of sight, reading then whenever I had some privacy. I had thought that by this time I knew a good deal about the history of U.S. policy in Vietnam, but there were revelations here that were startling, facts that we in the peace movement had claimed as true but only now found corroborated, in these documents, by the government itself.

Dan had given a copy to Neil Sheehan, a New York Times reporter he had met in Vietnam. But months had passed and nothing had happened.

One Saturday evening in June 1971, Dan and Pat and Roz and I planned to go to a movie. When they arrived at our place in Newton, Dan was clearly agitated. He had just phoned someone at the Times (not Neil Sheehan) about some matter, and been told that this was not a good time to talk because something odd was happening; the Times had put security guards all around the building and the presses were going full blast for the Sunday edition, printing some top-secret government document.

“You should be happy,” we told Dan. “They’re finally doing it.”

“Yes, but I’m pissed off — they should have told me.”

The next morning’s New York Times carried a large headline running across three columns: “Vietnam Archive: Pentagon Study Traces 3 Decades of Growing U.S. Involvement.” The story itself covered six pages of commentary and documents. It did not say where the Times had secured the material, and it took several days before the FBI traced it to Daniel Ellsberg. But Dan was out of sight, underground (actually, housed by various friends in Cambridge), and distributing more copies of the Pentagon Papers to the Washington Post and the Boston Globe while the Nixon administration was asking the federal courts to stop publication on grounds of “national security.”

The next morning’s New York Times carried a large headline running across three columns: “Vietnam Archive: Pentagon Study Traces 3 Decades of Growing U.S. Involvement.” The story itself covered six pages of commentary and documents. It did not say where the Times had secured the material, and it took several days before the FBI traced it to Daniel Ellsberg. But Dan was out of sight, underground (actually, housed by various friends in Cambridge), and distributing more copies of the Pentagon Papers to the Washington Post and the Boston Globe while the Nixon administration was asking the federal courts to stop publication on grounds of “national security.”

Twelve days later, Dan turned himself in at Post Office Square in Boston, where a large crowd of supporters, journalists, and curious onlookers watched as the FBI, somewhat embarrassed because it had not been able to find him, saw him emerge from a car and took him into custody.

Two weeks after the New York Times story appeared, the Nixon administration lost its last appeal before the Supreme Court. The majority of the court found that the First Amendment prohibited “prior restraint,” that is, stopping any publication in advance. Some members of the Court pointed out, however, that after publication, criminal charges would be possible, and so the administration went to work..

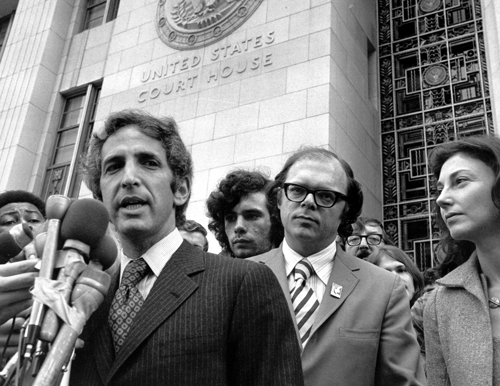

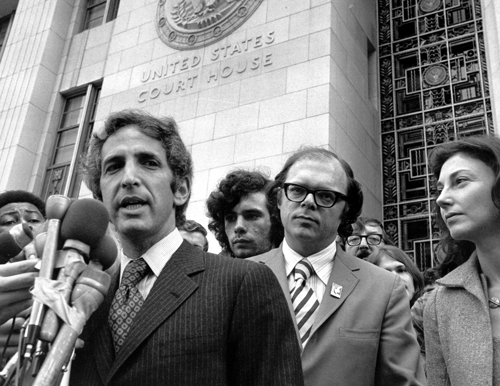

Images (2): Daniel Ellsberg and Anthony Russo at microphone and Ellsberg in Vietnam • Most Dangerous Man in America film website

Image: New York Times front page • Daniel Ellsberg website

More on the Pentagon Papers, Vietnam, and Anti-War Movements

The Most Dangerous Man in America: Daniel Ellsberg and the Pentagon Papers

Documentary film by Judith Ehrlich and Rick Goldsmith

The riveting story of how a Pentagon official risks life in prison by leaking 7,000 pages of a top secret report to the New York Times to help stop the Vietnam War. Read more at PBS.

The Most Dangerous Man in America Teaching Guide

Eight lessons for use with the documentary film about Daniel Ellsberg, the Pentagon Papers, the Vietnam War, and whistleblowing. Read more at the Zinn Education Project.

Camouflaging the Vietnam War: How Textbooks Continue to Keep the Pentagon Papers a Secret

While new U.S. history textbooks mention the Pentagon Papers, none grapples with the actual importance of the Pentagon Papers. Read more at the Zinn Education Project.

Vietnam: The Logic of Withdrawal

Originally published in 1967, this book helped sparked national debate on the war. It includes a powerful speech written by Zinn that President Johnson should have given to lay out the case for ending the war. This 2013 edition includes a new introduction by the author. Read more.

Mississippi Freedom Democratic Party’s Petition Against the War in Vietnam (July 28, 1965)

Lupe Fiasco reads from the Mississippi Freedom Democratic Party’s petition against the Vietnam War. Watch at Voices of a People’s History Vimeo page.

Teaching Resources on the Vietnam War and Anti-War Movements

Visit the the Zinn Education Project for resources on teaching the Vietnam War and on the theme of Wars and Anti-war Related Movements.

Category: Tags: Activist, Excerpts, Vietnam War, War