By Howard Zinn, from The Zinn Reader

Writing a column to appear in the July 4, 1975, issue of the Boston Globe, I wanted to break away from the traditional celebrations of Independence Day, in which the spirit of that document, with its call for rebellion and revolution, was most often missing. The column appeared with the title “The Brooklyn Bridge and the Spirit of the Fourth.”

The Brooklyn Bridge and the Spirit of the Fourth

In New York, a small army of policemen, laid off and angry, have been blocking the Brooklyn Bridge, and garbage workers are letting the refuse pile up in the streets. In Boston, some young people on Mission Hill are illegally occupying an abandoned house to protest the demolition of a neighborhood. And elderly people, on the edge of survival, are fighting Boston Edison’s attempt to raise the price of electricity.

So it looks like a good Fourth of July, with the spirit of rebellion proper to the Declaration of Independence.

The Declaration, adopted 199 years ago today, says (although those in high office don’t like to be reminded) that government is not sacred, that it is set up to give people an equal right to life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness and that if it fails to do this, we have the right to “alter or abolish it.”

The Declaration of Independence became an embarrassment to the Founding Fathers almost immediately. Some of George Washington’s soldiers resented the rich in New York, Boston, and Philadelphia, profiting from the war. When the Continental Congress in 1781 voted half pay for life to officers of the Revolution and nothing for enlisted men, there was mutiny in the New Jersey and Pennsylvania lines. Washington ordered two young mutineers shot “as an example.” The shovelfuls of earth covering their bodies also smudged the words of the Declaration, fives years old and already ignored, that “all men are created equal.”

Enslaved blacks in Boston took those words seriously, too, and, during the Revolution, petitioned the Massachusetts General Court for their freedom. But the Revolution was not fought for them.

It did not seem to be fought for the poor white farmers either, who, after serving in the war, now faced high taxes, and seizure of homes and livestock for nonpayment. In western Massachusetts, they organized, blocking the doors of courthouses to prevent foreclosures. This was Shays’ Rebellion. The militia finally routed them, and the Founding Fathers hurried to Philadelphia to write the Constitution, to set up a government where such rebellions could be controlled.

Arguing for the Constitution, James Madison said it would hold back “a rage for paper money, for an abolition of debts, for an equal division of property, or for any other improper or wicked project…” The Constitution took the stirring phrase of the Declaration, “life, liberty and the pursuit of happiness” and changed it to “life, liberty and property.” The Declaration was only a historic document. The Constitution became the law of the land.

Both documents were written by whites. Many of these were slaveholders. All were men. Women gathered in 1848 in Seneca Falls, New York, and adopted their own Declaration: “We hold these truths to be self-evident: that all men and women are created equal…”

The Constitution was written by the rich, who set up a government to protect their property. Gerald Ford is still doing it. They say he is a “good guy.” He certainly has been good to big business. He has arranged for gasoline prices and heating bills to go up while the oil companies make enormous profits. He vetoed a bill to allow an interest rate for homeowners of 6 percent while the nation’s ten biggest banks made $2 billion in profits last year.

Unemployment, food, and rent are all rising; but $7 billion in tax breaks went to 160,000 very wealthy people last year, according to a congressional report.

No wonder the spirit of rebellion is growing. No wonder that even police, paid to be keepers of law and order and laid-off when they have served their purpose, are catching a bit of that spirit.

It is fitting for this Fourth of July, this anniversary of the Declaration of Independence.

From Chapter 6, “Means and Ends,” in The Zinn Reader: Writing on Disobedience and Democracy.

More on Independence in the United States

A Fourth of July Commentary

“So it is fitting, at a time when police are exonerated in the killing of unarmed black men, when the electric chair and the gas chamber are used most often against people of color, that we refrain from celebration and instead listen to Douglass’ sobering words.” Continue reading.

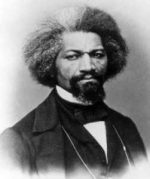

Frederick Douglass’ “The Meaning of the Fourth of July for the Negro”

Danny Glover reads Frederick Douglass’ speech at the Japanese American Cultural and Community Center George and Sakaye Aratani Japan America Theatre, Los Angeles, California, Oct. 5, 2005. Watch at the People Speak on Vimeo.com.

A People’s History of the United States: 1492 – Present

Since its original landmark publication in 1980, A People’s History of the United States has been chronicling U.S. history from the bottom up. Continue reading.

People’s History of Fourth of July

Read a collection of people’s history stories from July 4 that go beyond 1776 at the Zinn Education Project.

Category: Tags: Activism, American Revolution, Civil Disobedience, Essays and Speeches, Heroes, Holidays, Mainstream Media