For Thanksgiving, we highlight Native American resistance that caught the nation’s attention in the 1960s and 70s. As Howard Zinn wrote in Chapter 19 of A People’s History of the United States, “Never in American history had more movements for change been concentrated in so short a span of years.” Following are additional resources on Native American history and resistance.

Photo by Ilka Hartmann.

Photo by Ilka Hartmann.

For a time, the disappearance or amalgamation of the Indians seemed inevitable—only 300,000 were left at the turn of the century, from the original million or more in the area of the United States. But then the population began to grow again, as if a plant left to die refused to do so, began to flourish. By 1960 there were 800,000 Indians, half on reservations, half in towns all over the country.

The autobiographies of Indians show their refusal to be absorbed by the white man’s culture. One wrote:

Oh, yes, I went to the white man’s schools. I learned to read from school books, newspapers, and the Bible. But in time I found that these were not enough. Civilized people depend too much on man-made printed pages. I turn to the Great Spirit’s book which is the whole of his creation….

A Hopi Indian named Sun Chief said:

I had learned many English words and could recite part of the Ten Commandments. I knew how to sleep on a bed, pray to Jesus, comb my hair, eat with a knife and fork, and use a toilet. … I had also learned that a person thinks with his head instead of his heart.

Chief Luther Standing Bear, in his 1933 autobiography, From the Land of the Spotted Eagle, wrote:

True, the white man brought great change. But the varied fruits of his civilization, though highly colored and inviting, are sickening and deadening. And if it be the part of civilization to maim, rob, and thwart, then what is progress? I am going to venture that the man who sat on the ground in his tipi meditating on life and its meaning, accepting—the kinship of all creatures, and acknowledging unity with the universe of things, was infusing into his being the true essence of civilization….

As the civil rights and antiwar movements developed in the 1960s, Indians were already gathering their energy for resistance, thinking about how to change their situation, beginning to organize. In 1961, five hundred tribal and urban Indian leaders met in Chicago. Out of this came another gathering of university-educated young Indians who formed the National Indian Youth Council. Mel Thorn, a Paiute Indian, their first president, wrote:

There is increased activity over on the Indian side. There are disagreements, laughing, singing, outbursts of anger, and occasionally some planning…. Indians are gaining confidence and courage that their cause is right. The struggle goes on…. Indians are gathering together to deliberate their destiny . . . .

Around this time, Indians began to approach the United States government on an embarrassing topic: treaties. In his widely read 1969 book, Custer Died for Your Sins, Vine Deloria Jr., noted that President Lyndon Johnson talked about America’s “commitments,” and President Nixon talked about Russia’s failure to respect treaties. He said: “Indian people laugh themselves sick when they hear these statements.”

Around this time, Indians began to approach the United States government on an embarrassing topic: treaties. In his widely read 1969 book, Custer Died for Your Sins, Vine Deloria Jr., noted that President Lyndon Johnson talked about America’s “commitments,” and President Nixon talked about Russia’s failure to respect treaties. He said: “Indian people laugh themselves sick when they hear these statements.”

Around this time, Indians began to approach the United States government on an embarrassing topic: treaties. In his widely read 1969 book, Custer Died for Your Sins, Vine Deloria Jr., noted that President Lyndon Johnson talked about America’s “commitments,” and President Nixon talked about Russia’s failure to respect treaties. He said: “Indian people laugh themselves sick when they hear these statements.”

The United States government had signed more than four hundred treaties with Indians and violated every single one. For instance, back in George Washington’s administration, a treaty was signed with the Iroquois of New York: “The United States acknowledge all the land within the aforementioned boundaries to be the property of the Seneka nation….” But in the early sixties, under President Kennedy, the United States ignored the treaty and built a dam on this land, flooding most of the Seneca reservation.

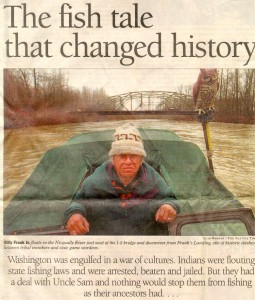

Resistance was already taking shape in various parts of the country. In the state of Washington, there was an old treaty taking land from the Indians but leaving them fishing rights. This became unpopular as the white population grew and wanted the fishing areas exclusively for themselves. When state courts closed river areas to Indian fishermen, in 1964, Indians had “fish-ins” on the Nisqually River, in defiance of the court orders, and went to jail, hoping to publicize their protest.

Resistance was already taking shape in various parts of the country. In the state of Washington, there was an old treaty taking land from the Indians but leaving them fishing rights. This became unpopular as the white population grew and wanted the fishing areas exclusively for themselves. When state courts closed river areas to Indian fishermen, in 1964, Indians had “fish-ins” on the Nisqually River, in defiance of the court orders, and went to jail, hoping to publicize their protest.

A local judge the following year ruled that the Puyallup tribe did not exist, and its members could not fish on the river named for them, the Puyallup River. Policemen raided Indian fishing groups, destroyed boats, slashed nets, manhandled people, arrested seven Indians. A Supreme Court ruling in 1968 confirmed Indian rights under the treaty but said a state could “regulate all fishing” if it did not discriminate against Indians. The state continued to get injunctions and to arrest Indians fishing. They were doing to the Supreme Court ruling what whites in the South had done with the Fourteenth Amendment for many years—ignoring it. Protests, raids, arrests, continued into the early seventies. Continue reading.

More on Native American Resistance and Struggle

Teaching Resources on Native Americans

Visit the the Zinn Education Project for resources on Native Americans.

Chief Joseph’s Account of His Trip to Washington, D.C. in 1879

Q’Orianka Kilcher reads Chief Joseph’s 1879 speech. Recorded, February 1, 2007, at All Saints Church, Pasadena, CA. Watch at The People Speak on Vimeo.com.

Tecumseh’s Speech to the Osages (Winter 1811-1812)

Deepa Fernandes reads Tecumseh’s speech on March 10, 2007, at The Great Hall at Cooper Union, New York, NY. Watch at The People Speak on Vimeo.com.

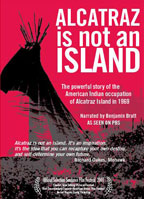

Alcatraz Is Not an Island

Documentary film on a small group of Native American students and “Urban Indians” who occupied Alcatraz Island in November 1969, and how it forever changed the way Native Americans viewed themselves, their culture and their sovereign rights. Read more at the Zinn Education Project.

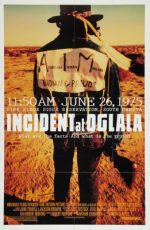

Incident at Oglala

Documentary film about the 1973 Wounded Knee incident and the conviction of Native American activist Leonard Peltier. Read more at the Zinn Education Project.

Category: Tags: Excerpts, Holidays, Native Americans