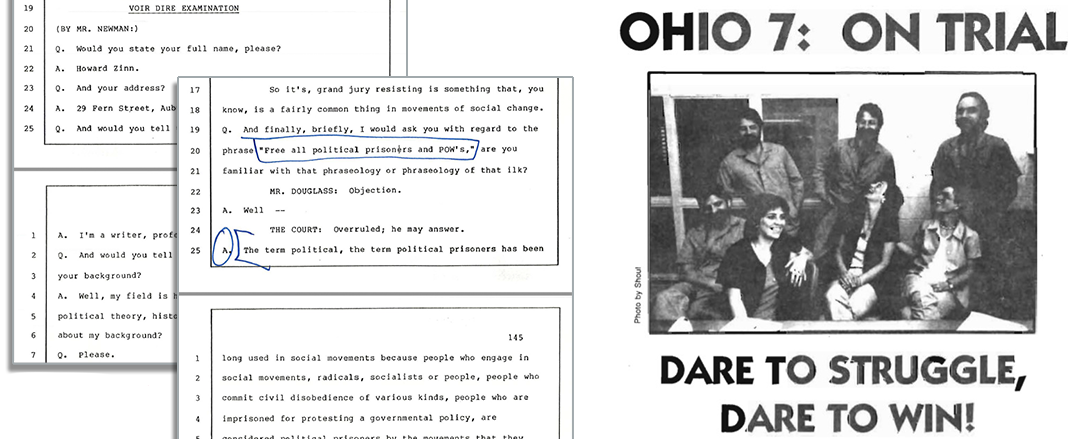

On October 18, 1989, Howard Zinn took the stand in defense of the United Freedom Front offering a definition of political prisoners during a record-breaking sedition trial in Massachusetts. Much like he did in other well-known defense cases, Zinn defended civil disobedience and direct action against forces that infringed upon civil liberties and democracy.

The following is Zinn’s court testimony available here as a PDF to download and transcribed below. Read more about the United Freedom Front at Howard Zinn and the United Freedom Front Sedition Trial.

Citation: Raymond Luc Levasseur Trial Transcripts (MS 334). Special Collections and University Archives, University of Massachusetts Amherst Libraries.

Transcript

Note: This is a portion of the fuller court transcription. In this section, Howard Zinn's responses are identified as "A." or "THE WITNESS." The defense lawyer is William Newman. His voice is identified as Q. The prosecutor is David Douglass and the presiding judge is William G. Young.

HOWARD ZINN, Sworn

(BY MR. NEWMAN:)

VOIR DIRE EXAMINATION

Q. Would you state your full name, please?

A. Howard Zinn.

Q. And your address?

A. 29 Fern Street, Auburndale, Massachusetts.

Q. And would you tell us, please, what your occupation is?

A. I’m a writer, professor emeritus at Boston University.

Q. And would you tell us, please, what your field is and your background?

A. Well, my field is history and political science, political theory, history of social movements. You asked about my background?

Q. Please.

A. And, ah, you’re talking about my educational background?

Q. Yes.

A. I did my undergraduate work at New York University and my graduate work at Columbia University. I got my MA. and Ph.D. at Columbia University. I did post-doctoral work at Harvard University. I taught for seven years, chairman of the history department at Spellman College in Atlanta, Georgia. And then became professor of political science at Boston University where I was from 1964 until last year.

And I’ve written various books and articles on history, history of social movements, on philosophy of civil disobedience, and generally on American history.

Q. In addition to your association in Boston, you’ve been a visiting professor at various institutions?

A. I’ve been a visiting professor three times at the University of Paris. I’ve lectured at other universities abroad, but I was a visiting professor in Paris, yeah.

Q. Have you been the recipient of various prizes and awards?

A. Yes. Several. My, my, my first book, LaGuardia in Congress, was a winner of the Albert Beveridge Prize of the American Historical Association. And I received grants from the Ford Foundation and the Eleanor Roosevelt Foundation and the American Philosophical Association.

Q. And you mentioned that you have published books. Would you tell us, approximately, how many books you have written or edited and published?

A. Ten or eleven books depending on how you count them.

Q. And those are in the fields you’ve described to us so far?

A. Yes. History, political science, political theory.

Q. And in addition to the books you’ve written, have you written a variety of essays that have been included in books?

A. Yes.

Q. And would you tell us approximately how many?

A. Oh, I don’t know, about, maybe about 30 essays in books and about 50 or 70 or 80 articles in journals and magazines.

Q. And over what period of time have those articles been published?

A. Oh, roughly from, I guess, 1959 to the present.

Q. And in addition to those writings, have you also written and published a number of book reviews?

A. Yes. Yes.

Q. And would you tell us approximately how many book reviews you have written and been published?

A. Well, maybe 15 or 20, 25.

Q. And have any of your works been translated abroad?

MR. DOUGLASS: Objection, your Honor.

THE COURT: Sustained.

Q. With regard to the works which you have written and published, have any of them dealt with political subjects?

A. Well, they’ve all dealt with, they’ve all dealt with political subjects of one sort or another.

I don’t know if you want me to be more specific, but the, my, well, my first book, LaGuardia in Congress, dealt with the very orthodox politics of a congressman in the 1920’s and early 1930’s when LaGuardia was serving in Congress.

I then wrote two books about the South and about the race question dealing with the Civil Rights Movement and dealing with the question of race. The book called SNCC: The New Abolitionists about one of the civil rights organizations of young people in the South, although The Southern Mystique dealt with problems of race in the South.

I wrote a book called New Deal Thought which was a book about the political ideas surrounding the New Deal, the political thought of not only the New Dealers but of various currents and movements surrounding the New Deal. Wrote a book —

MR. DOUGLASS: Objection, your Honor. To the extent that this is to establish the witness’s credentials, the United States doesn’t dispute he’s an eminently qualified professor.

THE COURT: Well, qualified on what? What don’t you dispute?

MR. DOUGLASS: I don’t dispute his qualifications as a professor.

THE COURT: I’m not, and I say this respectfully both to the witness and to you, I don’t know what that means. It seems undisputed he was for many years a professor at major institution, he taught college level courses. That’s undisputed.

MR. DOUGLASS: Yes. And that he has published many books in his field. He’s well versed in his field.

THE COURT: Which let’s be clear. What field is that, sir?

THE WITNESS: American history, history of social movements, political theory, political science.

THE COURT: You’re satisfied with that, Mr. Douglass?

MR. DOUGLASS: Yes. Not as to its relevance to this proceedings but as to that field.

THE COURT: He’s qualified —

MR. DOUGLASS: Yes.

THE COURT: — both to understand and teach those subjects?

MR. DOUGLASS: Yes, your Honor.

THE COURT: Go ahead, Mr. Newman.

Q. It’s fair to say, Professor Zinn, that you’ve had, you’ve devoted a great deal of your time to the study of political movements which are to the left of center?

MR. DOUGLASS: Objection.

A. Yes.

THE COURT: Sustained in that form.

Q. You’ve mentioned that you have studied and written about political movements. What type of political movements?

A. Well, I’ve, I’ve written about the abolitionists movement, about the anti-slavery movement before the civil war. In my — I wrote, as I mentioned before, I’ve studied and written about the Civil Rights Movement in the United States.

I wrote specifically when I wrote a book about Vietnam about the anti-war movement in the United States. In my book People’s History of the United States, which is a comprehensive survey of social movements. I’ve written about the, about the movements of the colonial period, the movements of rebellion, uprising in the colonial period in the United States. Written about the agitation that went on in the years just before the revolution and during the revolutions. Wrote about the movements of protest, the tenants’ movement and the labor movement in the early 19th century. Wrote about the labor struggles in the United States from, well, from pre-civil war days up through the late 19th century, early 20th century, the New Deal period. Wrote about the Populist movement, the farmer struggles, the various farmer alliances. And wrote about the Socialist Party and the IWW, two radical organizations. I’ve written about anarchists in the United States in the early 20th century. I’ve written about the role of the Communist Party in the United States in the 1930’s, 1940’s, and during the period of 1950’s.

And I suppose in general I’ve, I’ve just done, I’ve done a lot of work and a lot of research and writing about social movements and particularly Left social movements in the United States.

Q. Now, with regard to any of the persons who are on trial here, do you personally know any of them?

A. No, I don’t.

Q. And I would like to show you —

MR. NEWMAN: Judge, for purposes of this hearing I’ll use a copy rather than take the Court document.

THE COURT: And that may be done so long as they’re identified adequately.

MR. NEWMAN: And what I am showing to Professor Zinn are the United Freedom Front communiques.

Q. Would you take a look at what I’ve just described for the record and the Court as the United Freedom Front communiques and tell us whether you have had the opportunity to look at those prior to this time?

A. Well, I received from you in the mail this past week I guess basically these, these same documents.

Q. Okay. And did you have a chance to read them?

A. I had a chance to read them, yes.

Q. Now, do you know who wrote them?

A. No.

Q. Now, based on your reading of them, can you tell us what you perceive them to be?

A. Well, they seem, obviously, kind of manifestoes, statements, declarations, documents that left-wing movements distribute and put out to the public in connection with whatever actions they’re engaging, and they’re intended to explain to the public why these movements are doing what they’re doing and intend to bring to the attention of the public some particular issue.

In the case of these communiques, they’re obviously trying to bring to the attention of the public the issues of South Africa, the issues of Central America, the issues of American foreign policy, of what they refer to as American imperialism, of the problem of racism in the United States and in other places, problem of corporate complicity, imperialism corporate complicity and what is happening in other countries. These are some of the issues that I remember them bringing up here.

And so the purpose of these, as I read them, I don’t know what, as I said, I don’t know the people who wrote these, but as I read them it seems clear to me that there are thousands and thousands and thousands of leaflets. I don’t know how many, tens of, hundreds of thousands of leaflets and communiques that have been distributed by various movements in the United States which have this sort of rhetoric about, about struggle, about revolution, about solidarity, about racism, about imperialism, about capitalism, about American foreign policy. And so let’s put it this way, I wasn’t very surprised when I, when I read the language of these communiques.

And it’s kind of very common for left-wing organizations. In fact, this is what they’re about. Left-wing organizations are trying to, to bring issues to the attention of the public that they, that the mainstream media and mainstream politics don’t put in the forefront. And so, the tendency is to use very strong rhetoric and very exciting words and very denunciatory language and revolutionary language. I mean, not all left-wing movements use revolutionary language.

MR. DOUGLASS: Objection, your Honor.

A. But what I see here is revolutionary language.

THE COURT: Well, wait just a moment.

THE WITNESS: Yeah.

THE COURT: There was an objection. I’ll entertain what else you had to say, but we’ll stop it at that point.

You ask another question, Mr. Newman.

MR. NEWMAN: Okay.

Q. If I might invite your attention to what is —

MR. NEWMAN: Just for your records, Judge, since we’re using a separate document, a separate piece of paper, it’s communique No. 10, United Freedom Front, Page 2.

Q. And inviting your attention to the bottom of it, I would ask you if you would take a look at what it says on the bottom and ask you if you are familiar with these terms as used by left-wing, left-wing groups?

A. You mean these slogans?

Q. Yes.

A. “Death to Apartheid,” “Victory to the Azanian People,” “South Africa out of Namibia,” “Defeat U.S. Imperialism and its Death Merchant Backers,” “Free all Political Prisoners” and –

THE COURT: Wait, wait, wait.

THE WITNESS: I’m sorry.

THE COURT: No, I have an extraordinarily good court reporter.

THE WITNESS: Oh.

THE COURT: He hasn’t said anything and he’s entitled to.

THE WITNESS: I’m sorry.

THE COURT: But I can’t keep up with that. So —

THE WITNESS: Okay. I was trying to get through it quickly, you know.

THE COURT: Well, we have to understand.

THE WITNESS: Sure.

THE COURT: And you’re trying to focus on what terms he’s asking you about.

THE WITNESS: Right.

THE COURT: Rather than recite them all —

THE WITNESS: Okay.

THE COURT: — have you looked at that paragraph?

THE WITNESS: Yes, actually it’s sort of a list of slogans.

THE COURT: I can see it.

THE WITNESS: Take them one at a time?

THE COURT: No, there’s a list of slogans. You’ve looked at each one?

THE WITNESS: Yes.

THE COURT: Go ahead, Mr. Newman.

Q. And can you tell us what opinion you came to with regard to those slogans when you read them?

THE COURT: I don’t understand the question. What opinion as to what?

MR. NEWMAN: Just a moment, please.

Q. Let’s, let’s just look at — look at the first one if we might, “Death to Apartheid.”

A. Yes.

Q. And ask you whether in your study and writing whether you’re familiar with that slogan?

A. I’ve heard it before. I’ve seen it on, I’ve seen it on picket signs where there have been demonstrations against apartheid in South Africa. And it’s, so that I’m, you know, it’s not the first time I’ve seen that slogan. It’s a very strong statement about apartheid.

Q. And are you familiar with that term as it’s been used by left-wing political groups in the country?

MR. DOUGLASS: Objection.

THE COURT: Sus — sustained in that form.

Q. Would you tell us how you’re familiar with that term other than what you’ve just told us?

MR. DOUGLASS: Objection.

THE COURT: No, overruled. He may tell us how he knows about the term.

A. Yeah. Well, I, I know the term as I said because I’ve seen the term used in literature, and I’ve seen the term used in demonstrations, and I know it as, as a statement about apartheid as, as a statement of intention to do away with apartheid in South Africa. And as a statement of support for whatever movements there are in South Africa that are opposed to apartheid. That’s how I understand that statement.

The word death, obviously apartheid is not a person, so the word, the word death is a very common term used in left-wing slogans which is, you know, because it’s an arresting word, it’s a dramatic word, and so “Death to Apartheid” is simply a very, very powerful way of saying we want to do away with apartheid. A more modest person would say “Do away with apartheid,” “Down with apartheid,” but there’s a tendency among some left-wing groups to use very strong language like that. But they mean basically the same thing.

Q. What about the slogan “Defeat U.S. imperialism and its death merchant backers”?

MR. DOUGLASS: Objection.

THE COURT: I was talking to the clerk. You’re going to have to ask it again.

MR. NEWMAN: Sure.

Q. With regard —

MR. NEWMAN: I’ll rephrase it, too, if I might.

Q. With regard to the slogan “Defeat U.S. imperialism and its death merchant backers,” in your study and writings, are you familiar with rhetoric or jargon of that ilk?

A. Well, yes. Defeat U.S. imperialism is a, well, been a very common term in that form and slightly other forms by movements that have been opposed generally to American foreign policy, to American intervention, basically opposed to American intervention of other countries. At the turn of the century, well, roughly around the time of the Spanish-American War and the years following the Spanish-American War, there was an anti-imperialist league in the United States. And the anti-imperialist league talked about doing away with ending U.S. imperialism. And they were talking about what the United States was doing in Cuba, what the United States was doing in Puerto Rico, what the United States was doing in the Philippines, the war carried on in the Philippines. And so defeat U.S. imperialism is, you know, I suppose a continuation or part of the sort of a general long history of left-wing opposition to American intervention in other countries. The phrase “death merchant backers,” well, I actually haven’t seen death merchant backers often in recent years but in —

MR. DOUGLASS: Objection.

THE COURT: No, he may finish his answer.

A. — but in around the time of World War I the term merchants of death became a very common term to refer to the munitions makers who were profiting from World War I. And so death merchants came to mean the corporations and the arms industry and the weapons manufacturers who were supporting imperialism, who were, who were involved in it.

So, those are the meanings of the term as I’ve seen it historically.

Q. What about the phrase “Build the revolutionary resistance movement”? Are you familiar based on your study and writing with that type of language?

A. Well, revolutionary resistance movement, these are, these are some of the common words used in left-wing rhetoric. The term revolutionary covers a wide range of possibilities and programs and left-wing groups which have even disputed one another’s position. They’ve all claimed the word revolutionary.

And so, to build a revolutionary movement means one thing to one organization, it means one thing to the Socialist Party. It means another thing to the IWW, it means another thing to people in the Populist movement who considered themselves revolutionaries. It means one thing to the Communist Party, one thing to the Socialist Workers Party. There are people in the Civil Rights Movement who consider themselves revolutionaries. And the different meaning, in fact, people talk about nonviolent revolution. People have written books about nonviolent revolution.

So, the term revolutionary has meant a very, very broad range of ideas which basically have to do with changing the system. How, exactly how the system will be changed, well, that varies from group to group.

Resistance movement, well, the term resistance has been used a lot, probably used a lot more in the last 30 years than years before that. But it has been used for a long time in American history to mean popular resistance to governmental policy. That’s what basically is meant. The, the creation of organizations that would oppose governmental policy both domestic and foreign and that would try to bring about change. During the anti-slavery days they used the term resistance. They used it in connection with the fugitive slave acts. Resist the fugitive slave acts. I mean the idea was don’t cooperate, don’t obey, break into courthouses, break into police stations, free the slaves so that they won’t be sent back to slavery. And the term resistance was used again and again in connection with the fugitive slave act, and were the actions of various groups at that time which were opposed to slavery and which, as I say, took very, very drastic action to violating the law, very militant action to free slaves who were being kept by the United States government for the southern slave owners.

Q. Directing your attention to the line above where it says United Freedom Front, where it says, “Solidarity in support to the locked down freedom fighters and grand jury resisters.”

In your study and writing, are you familiar with language of that ilk, or those phrases?

MR. DOUGLASS: Objection.

THE COURT: Overruled. He may answer.

A. Well, solidarity and support mean, of course, basically the same things. The term solidarity, of course, occurs a huge amount in the American labor movement. Of course, probably a lot of Americans think of it as a Polish phrase. But it’s a very American phrase, very much involved in the American labor movement, American labor songs, “Solidarity Forever.” And it all has to do with people getting together, people joining one another. And, of course, the basic idea being that, deprived of political power, deprived of economic power, the only weapon that people have, the only instruments that people have in order to bring about change are the unity, the solidarity of getting together of people. So solidarity, you know, has, has that sort of meaning historically.

And as I say support, support to the locked down freedom fighters, well, I haven’t seen the phrase locked down frankly. I don’t, I don’t know what locked down means except that I assume freedom fighters — well, I have, we all know the phrase freedom fighters has been used lots of times, especially in recent years to represent all sorts of people. But I assume the freedom fighters must mean people on the left who are, who are fighting for the causes that are represented in this document, and maybe locked down means that they’re locked up, which is a typical example of how words in these communiques may not mean exactly what they say.

And the last phrase in this is “grand jury resisters.” Well, this is, it’s a long standing thing in, I suppose more often in recent, in recent years, especially since the 1960’s, but it’s been true before then, that when prosecutions were taking place against people on the left, friends of theirs or the people themselves brought before grand juries, would very often refuse to talk, refuse to cooperate with the prosecution and they would refuse to talk and sometimes they would go to jail and sometimes spend long terms in jail. And so grand jury resisters is, you know, people in the Civil Rights, it happened in the Civil Rights Movement. I remember there was a nun who was the head of a Catholic school in New York who spent a long time in prison because she refused to talk to a grand jury about other nuns and priests who had engaged in anti-war actions. So it’s, grand jury resisting is something that, you know, is a fairly common thing in movements of social change.

Q. And finally, briefly, I would ask you with regard to the phrase “Free all political prisoners and POW’s,” are you familiar with that phraseology or phraseology of that ilk?

MR. DOUGLASS: Objection.

A. Well —

THE COURT: Overruled; he may answer.

A. The term political, the term political prisoners has been long used in social movements because people who engage in social movements, radicals, socialists or people, people who commit civil disobedience of various kinds, people who are imprisoned for protesting a governmental policy, are considered political prisoners by the movements that they come out of and very often by people outside those movements who recognize that they’ve been in prison not for common crimes but in prison basically for their ideas or for social actions intended to bring about change.

And so, the political, political prisoners is to be, is to be distinguished from people who are put in jail for ordinary crimes. They’ve been put in prison for political reasons. Of course, the United States government itself recognizes that distinction when it gives —

MR. DOUGLASS: Objection.

THE COURT: At this point the objection is sustained.

THE COURT: Go ahead.

THE WITNESS: Well —

THE COURT: No, go ahead, Mr. Newman, with another question.

MR. NEWMAN: Yes.

THE COURT: I sustained it, sir, because you were asked for your opinion and you gave it and then you began to illustrate it with other examples. I don’t impugn that as a teaching method, but listen to his questions and answer his questions fully. Go ahead, Mr. Newman.

Q. In your opinion, are there common characteristics of what you have called, I believe, agitational left-wing writings?

A. Yes.

MR. DOUGLASS: Objection.

THE COURT: No, no, he may have that. Your answer is “yes”?

THE WITNESS: Yes.

THE COURT: All right. Go ahead.

Q. And what’s your opinion on that?

A. The common characteristics of left-wing political writing, well, the common characteristics are that they are very, very agitational, very, well, often inflammatory, very often overblown or exaggerating, but the intention is always to arouse people and excite people and agitate people and provoke people. Because the people in these left-wing movements think, and I think they’re probably right, that they, they do not have access to the attention of people through normal mechanisms of communication, don’t have as much access to the press or to the media as other people have, so they put out these little leaflets, these [manifestos], trying to make up for their lack of communicating power by the power of their language and very often, therefore, by the exaggeration of their language and by, you know, the inflammatory nature of their rhetoric. And so, but the fundamental, their [fundamental] aim is to try to educate people about certain things that they feel that people don’t know, try to inform them, try to arouse them, try to get them to join organizations, try to get them to move them into action against policies that they think are wrong. And so, I mean that’s what they have in common. The policies that they concentrate on may vary from organization to organization, the actions that they’re trying to get people to engage in may differ from group to group, but the basic, the nature of the language, that is, the strong nature of the language is, that’s a common characteristic, and the intent of this language to arouse and provoke, that’s a common characteristic.

Q. And the, what have been described as the United Freedom Front communiques, is that within this genre that you’ve described?

A. It’s, it has those, it has those qualities that I’ve just described, certainly. More yeah, stronger than most of the communications you’ll see on the left, but not odd and not, not surprising and within the range, within the range of left-wing rhetoric as it has been historically.

MR. NEWMAN: May I have just a moment please, Judge.

THE COURT: You may.

(Pause.)

Q. Without going through them all, in addition to what we’ve entitled United Freedom Front communiques, did you have the opportunity to review documents that had on the front what were called Sam Melville. They’re in this packet but in the documents I had delivered to you, the Sam Melville-Jonathan Jackson unit communiques? I could show them to you.

A. Yeah. I don’t remember anything. If you showed them to me, I can tell you whether I’ve seen them.

Yeah. Yeah. I recognize especially those pages that are so badly printed I can’t read anything. But, yeah, I, I guess this was part of what you sent me, yeah.

Q. And without going through these page by page, in general, what you’ve said with regard to the use of language in the United Freedom Front communiques, would that apply as well to the Sam Melville-Jonathan Jackson unit communiques?

A. Yeah. Basically the same, yes.

MR. NEWMAN: Thank you very much, and thank you for coming.

THE COURT: Sir, you may step down while we discuss the issue. And if you would go out to the witness room and we’ll —

(Whereupon the witness stepped down.)