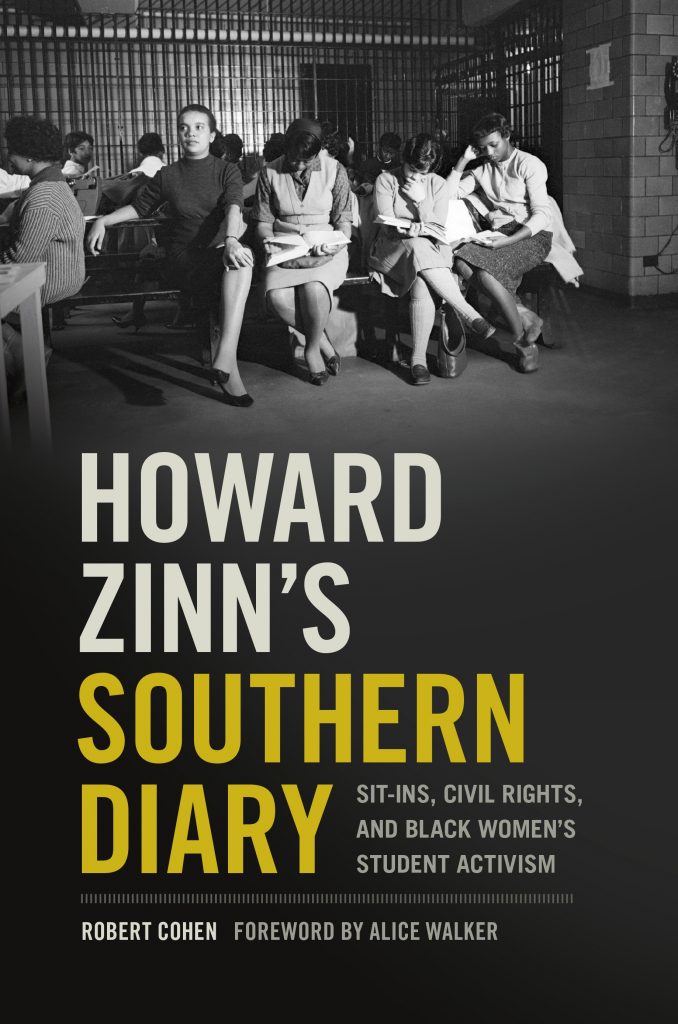

The University of Georgia Press has published Howard Zinn’s Southern Diary: Sit-Ins, Civil Rights, and Black Women’s Student Activism by Robert Cohen with a foreword by Alice Walker. The book includes diary entries from Howard Zinn’s time teaching at Spelman College (1956-1963). Historian Robert Cohen offers a substantial overview of Zinn’s role at Spelman and other archival documents.

The University of Georgia Press has published Howard Zinn’s Southern Diary: Sit-Ins, Civil Rights, and Black Women’s Student Activism by Robert Cohen with a foreword by Alice Walker. The book includes diary entries from Howard Zinn’s time teaching at Spelman College (1956-1963). Historian Robert Cohen offers a substantial overview of Zinn’s role at Spelman and other archival documents.

Below are excerpts from Cohen’s overview and the diary entries. Visit the Zinn Education Project to read a transcript excerpt from Zinn’s debate with E. Fulton Lewis III, House of Un-American Activities Committee research director.

Mentor to the Movement

This excerpt (pages 3-6) is from Robert Cohen’s overview, “Mentor to the Movement,” in Howard Zinn’s Southern Diary.

. . . [Howard] Zinn’s involvement with the Atlanta student movement and his closeness to Spelman’s leading student and faculty activists gave him an insider’s view of that movement and of the political and intellectual world of Spelman, Atlanta University Center, and SNCC. Thus it was no surprise that Zinn would write the first nationally circulated accounts of the Spelman movement in the Nation and then in his book The Southern Mystique (1964); the most detailed contemporary report on the black freedom struggle and its segregationist foes in Albany, Georgia (for the Southern Regional council), Albany: A Study in National Responsibility (1962); and the first book-length history of SNCC, SNCC: The New Abolitionists (1964). Zinn would always view his years at Spelman (1956-63), which connected him to the civil rights movement and a remarkable generation of Spelman students, as among the most significant in his life, which is why he devoted the first three chapters in his memoirs to that time.

It is only now, however, well after Zinn’s death in 2010, and the opening of his papers at New York University’s Tamiment Library, that we can see that some of his most memorable writing on his Spelman days are from a daily journal he kept in his last semester there, during the winter-spring of 1963, which he never published. Not even his close friends, students, and colleagues at Spelman in that era were aware at the time that Zinn was keeping a diary. It was only with the publication of Zinn’s memoir in 1994 that the existence of the journal was even mentioned publicly–when he quoted from it as he narrated the story of his escalating conflict with the Spelman administration that led to his firing in June 1963. Similarly, historian Martin Duberman, drew on the diary to go over this same story in his biography, Howard Zinn: A Life on the Left (2012). Most recently, historian Staughton Lynd, a close friend and colleague of Zinn in his last three years at Spelman, used excerpts from the diary in an insightful essay on Zinn in his book Doing History from the Bottom Up (2014), in which he shows that Zinn thought strategically and deeply about the ways that legal change and interracial contact could overcome old patterns of racial discrimination.

Mere excerpts from the diary cannot, however, do justice to its historical significance. Read from start to finish, the diary, which has more than fifty entries on the student and faculty conflicts with the Spelman administration, is one of the most extensive records of the political climate in in a historically black college in 1960s America – a time when students at those colleges were on the cutting edge of that decade’s new student activism. Insightful as Zinn’s memoir and Duberman’s biography of Zinn are on his battles at Spelman, the unabridged diary offers a more in-depth view than either of the book chapters – recording in real time the free speech, academic freedom, and student rights battles that rocked Spelman in 1963 and led to Zinn’s firing and the abrupt ending of his Spelman years. The diary, in other words, merits publication because it illuminates far more than Zinn’s own story. It captures a pivotal time in the history of student protest in the 1960s, foregrounding the activism of African American young women and capturing the way race was lived in Atlanta–the relationships between that city’s black and white academics and activists and their generational and ideological tensions when the most idealistic among them were engaged in historic desegregation struggles. Zinn in Atlanta during the early 1960s was, as his wife Roslyn wrote their friends Ernie and Marilyn Young, “in the right place and at the right time.” Zinn had been at Spelman since 1956. But beyond this, he was a gifted writer and searing social critic who would go on later in the 1960s to write widely circulated books opposing the Vietnam War and defending civil disobedience, and in the 1980s he published the best-selling radical history of his time, A People’s History of the United States. So by 1963 even his immediate responses in his diary to the events he observed and was a part of in Atlanta, both on and off campus, were written with great clarity, and carried with them the insights of a veteran movement activist who had longstanding friendship in black Atlanta and had lived and taught in that community for years. For Zinn, living and teaching on a historically black college campus had opened a window onto black America to which few whites had access. Even when the Zinn diary’s accounts of events are incomplete or less than entirely persuasive, they often raise important questions about social and political life at a historically black women’s college and how this conversation institution navigated a time when its students became central actors in a revolution in southern race relations.

Zinn’s journal offers a vivid view of Spelman student activism during one of its most significant yet least well-known phases. Most of the historical writing on and commemorations of the Atlanta student movement and Spelman student protest have been devoted to the sit-in movement, especially in 1960, the historic first year when demonstrations in downtown Atlanta brought about the initial cracks in the Jim Crow line in Atlanta stores and eateries. By the time Zinn was recording his diary during the winter-spring semester of 1963, Spelman students and other activists from the Atlanta University Center, joined by a core of white progressives from Emory University, were engaged in a series of sit-ins and demonstrations to follow up on those of prior years, since the majority of restaurants and hotels in Atlanta—despite the desegregation agreement brokered by the city’s Chamber of Commerce president on 1961—were still racially segregated. While for Spelman students this ongoing struggle for racial justice remained central, they became increasingly engaged with a second kind of freedom struggle—one that occurred not downtown but on their own campus and that was about personal freedom, gender liberation, and free speech. They were seeking to end the paternalistic policing of their social lives by an overbearing administration, which treated them as though they were immature girls who needed constant chaperoning and rigid curfews and sought to suppress their free speech rights whenever they dared to protest these and other restrictions.

Here, as Zinn’s diary shows so clearly, you had Spelman students who had played very adult roles, committing civil disobedience downtown, getting arrested, and even risking their lives in sit-ins against Jim Crow, but on their own campus these young women were still regimented like children. This contradiction seemed increasingly glaring and intolerable to the college’s student activists. As Spelman civil rights activist Brenda Cole recalled, after the second wave of sit-ins during the fall of 1960-61 secured the rights of African Americans to be served on a nondiscriminatory basis at some of Atlanta’s largest commercial establishments, such as Rich’s department store, she and her classmates “started looking around saying ‘what has it profited us to go to Rich’s when [because of Spelman’s restriction on students traveling downtown] we’ve got to get five or six girls to go with us? We can’t even leave campus after a certain time or . . . .ride in cars . . . Then we started looking at the . . . rules on campus . . a lot closer and said . . . ‘we’re still not free.’” Activists at Spelman became convinced, as student movement veteran Lana Taylor (Sims) explained, that their college was “just too paternalistic. That you have women who. . . couldn’t go around the corner by themselves . .. The institution was just working against the thing that they were supposed to be fostering—growing up and maturity.’” And so the struggle against racial discrimination downtown, and its liberatory ethos, fostered a critique and revolt against gendered restrictions of their campus lives at Spelman.

Diary Entries: 1963

Excerpted from pages 155-156 of Howard Zinn’s Southern Diary.

Thurs. May 9

David McReynolds of FOR [Fellowship of Reconciliation] visiting Staughton [Lynd] so he visited our class. Spoke to my Russian class on lawn, on disarmament. Realized at one point how many members of this 12 person class involved. Guy and Candy Carawan just back from Birmingham jail. Anna Jo Weaver just out of Fulton Cy. Jail. Betty S. a veteran of 14 days in jail. One fourth of [the] class.

Fri. May 10

An unprecedented meeting, from about noon to about 4 PM, took place today out on the Emory [University] quadrangle. A few Liberal Club students called it, to discuss informally, with no specific program of action, the events in Birmingham and elsewhere in connection with integration. About ten of our students went, including Anna Jo Weaver, Davis Satcher, Dot Myer, Robt Allen. Ralph Moore spoke at length. They had expected some trouble but there was none. Antagonistic questions, but nothing approaching violence. At one time 150-200 students were sitting on the grass listening. All in all, far more successful than anyone had anticipated. And Emory Univ. officials made no move to break it up. After it was over a faculty couple invited the Negroes home, followed by a score of white students. They brought in a keg of beer and had a ball.

Jeff gave an oral report in his class on Thoreau’s Walden. His teacher gave him an A plus, asked him to repeat it at her 11th grade class. The 11th graders gave him grades and comments on it—almost all A’s and praising it. One girl gave him an F, saying, “No eighth-grader could read Walden and understand it. I don’t believe you read that book.”

Myla’s English teacher told the class to write on “something I care deeply about.” Most wrote on integration—something that wouldn’t have happened two years ago (maybe not even two weeks ago—maybe the headlines have had this effect). Most against. But four or five for, and very bold. One girl said: “If I had Martin Luther King here I’d shoot him, and a few paragraphs on spoke of Negroes committing murder and said, ‘Don’t they know the Bible says Thou Shalt Not kill.‘” The class snickered at her obvious inconsistency, and the teacher called attention to it too.

Jeff’s math teacher mentioned I’d been quoted in Newsweek, got into [a] discussion with Jeff on integration. Turned out she’s from Albany, Georgia.

Related Resources

Howard Zinn’s Southern Diary: Excerpts

Howard Zinn’s Southern Diary: Excerpts

The University of Georgia Press has published Howard Zinn’s Southern Diary: Sit-Ins, Civil Rights, and Black Women’s Student Activism by Robert Cohen with a foreword by Alice Walker. The book includes diary entries from Howard Zinn’s time teaching at Spelman College (1956-1963). Historian Robert Cohen offers a substantial overview of Zinn’s role at Spelman and other archival documents. Read more.